A student contribution to the REU blog.

My research this summer investigated how mosquito abundances vary with temperature and habitat. Mosquitos lay their eggs in water, and they must remain submerged in order to mature successfully. Rural habitats are beneficial for mosquitos because they tend to be rich in plants that offer both shade and food for mosquito larvae. Cities also provide suitable habitat, and they tend to be warmer than nearby rural areas. Warmer temperatures help mosquitos grow faster. Because mosquitos do especially well in warm temperatures, I hypothesized that more mosquitos would be found in cities than surrounding rural areas.

To investigate which mosquito species thrive with different landcover types, I analyzed data on mosquito species and abundance at sites from the Baltimore Ecosystem Study that span an urban to rural gradient. The data at 10 sites in Baltimore County and City from 2011-2015. Researchers placed ‘ovitraps’ – plastic cups that mosquitos lay their eggs in – at a variety of sites. These eggs hatched into larvae, allowing the research team to count and identify species in the ovitraps.

Land cover at the sites varied from rural forest to city, and some sites featured a mix of plants and manmade surface cover like sidewalks and roads. Temperature was monitored at each site using ‘iButtons’ – small sensors that can be placed on the bottom of an ovitrap, which record temperature hourly. Site temperature varied according to landcover. The table below shows temperature trends at each type of site. Rural sites were coolest; urban sites were warmest. Suburban and urban-green sites, located between distinctly ‘city’ and ‘rural’ areas, had temperature trends that reflected this positioning: cooler than city sites, warmer than rural sites.

| Mean Temperature by Site Type | |

|---|---|

| Site Category | Mean Temp (C°) |

| Rural | 19.59496 |

| Suburban | 20.31396 |

| Urban-Green | 20.41665 |

| Urban | 23.25141 |

I analyzed these data by creating plots and models, and running statistical tests. This helped me compare mosquito abundance and diversity among the sites, with respect to differences in temperature and physical attributes like vegetation and land cover.

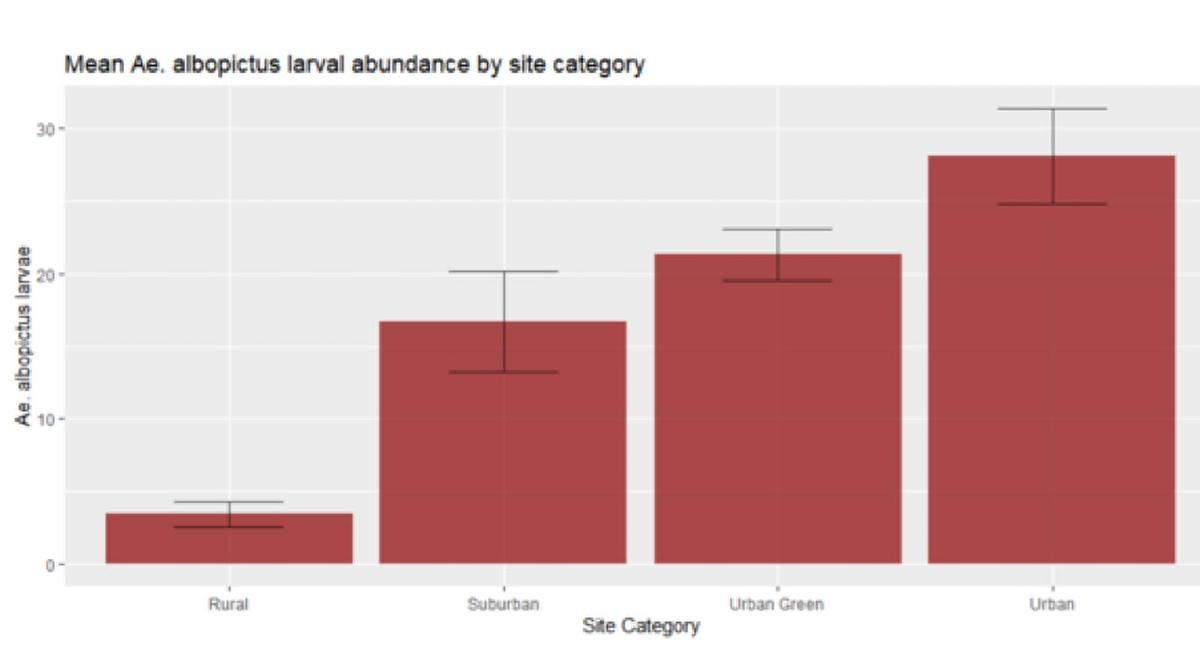

Some mosquito species we collected, like Aedes albopictus, also known as the tiger mosquito, are a public health concern. This is because they bite people and can spread diseases like dengue, chikungunya, and Zika virus. The results of this study shed light on mosquito habitat preferences among species. The barplot below compares how many tiger mosquito larvae were found at each site. Urban sites had more larvae and are therefore likely to also host more adult mosquitos.

Tiger mosquitos may be more common at city sites because they are warmer and have more small egg-laying habitats than rural areas. For example, places with lots of human activity have more artificial water-holding habitats like gutters, flower pots, garbage heaps – anything that can hold water can be a potential egg-laying habitat. There are also more people to provide blood meals for hungry mosquitos. By researching what parts of a habitat increase and decrease the number of mosquitos within it, we can better understand how to control mosquito populations. Researching which communities are more at risk can help us to determine where we should spray insecticides. This is important to stopping the spread of disease in areas where especially risky mosquito species, like tiger mosquitoes, pose an outsized threat.

MyKenna Zettle, a student at University of Pittsburgh at Bradford, participated in Cary Institute's 2020 Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) program. This summer, MyKenna worked with Cary scientist Shannon LaDeau to study effects of microclimate and local weather on mosquito populations in Baltimore, Maryland.