In July, Dutchess County celebrated Watershed Awareness Month. Throughout the region, educational activities highlighted the role that watersheds play in protecting the health of freshwater resources. When watersheds are compromised—typically through alterations to the landscape, such as sprawling development, intensive agriculture, or improper waste disposal—adjacent water bodies suffer.

The "watershed approach" is the best scientific tool available for understanding how the condition of a watershed influences the quality of nearby lakes, streams, rivers, or bays. By considering all the factors that affect a particular water body, the watershed approach reveals how things are connected in the environment. This, in turn, provides a roadmap for appropriate cleanup and protection efforts.

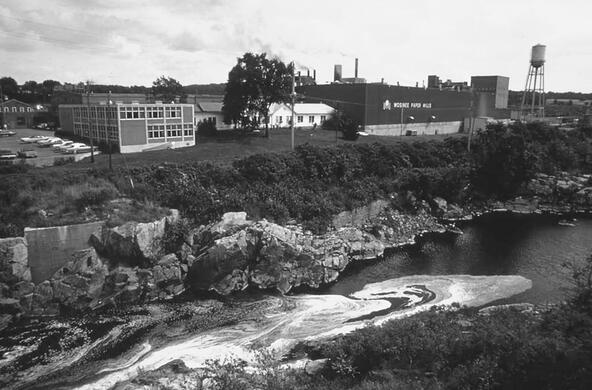

It is common to encounter multiple pollutant sources in a given watershed, some of which are difficult to control. "Point source" pollutants originate from an easily-identified source, such as a pipe or ditch. Examples include sewage treatment plant and factory discharges. Because these pollutants can be traced back to a single source, they can be treated and regulated.

"Non-point source" pollutants are more diffuse in nature and harder to address. They occur when rain or snowmelt moves across the landscape, collecting pollutants from a large area, which may include roadways, developments, industrial sites, lawns, and agricultural fields. During its journey through the watershed, runoff accumulates things like fertilizers, insecticides, microorganisms, fossil fuels, and heavy metals. These pollutants are then deposited in nearby water bodies, to the detriment of water quality and aquatic life.

Like many environmental problems, watershed management is complicated by the fact that we typically want to accommodate competing needs. This creates conflicts and tradeoffs. For example, how can we balance the need for grazing animals to drink from a stream with the desire to maintain shady stream banks that promote trout habitat? We want farms and trout; figuring out how to get them both in the same watershed isn't easy.

No one knows the complex nature of watershed management better than the scientists and stakeholders working with the Chesapeake Bay Program. The Chesapeake Bay is the largest estuary in the United States and the focus of the country's most ambitious watershed management program. While the Bay conjures up images of blue crabs and open water, its watershed stretches across more than 64,000 square miles, including parts of New York State and Pennsylvania.

The Chesapeake Bay Program was formed in 1983 as a response to collapsing crab and oyster harvests, rampant algal blooms, and the overall degradation of the Bay. It has emerged as a signature program in environmental management. In an effort to improve conditions, multiple states (Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, Pennsylvania, and New York) have set specific goals for reducing pollution, restoring habitats, and protecting watershed land.

As part of the Chesapeake Bay Program, sewage treatment plants have been upgraded and best management practices have been implemented on agricultural fields across the watershed. Bay partners are also working to protect intact watershed land, restore fish passages and degraded wetlands, and develop ecosystem-based fishery management plans.

Perhaps most importantly, an extensive monitoring and modeling program has been developed to assess progress towards both program goals and our scientific understanding of how the Bay ecosystem functions. And yet, after more than 25 years of work, many of the Chesapeake Bay Program's goals have not been met.

This has caused some to wonder if the scientists and managers are on the right track. But the fact is, we have learned a lot, including the sad reality that-once degraded-aquatic systems can be slow to recover. Watershed clean-up efforts have not been fruitless, their impact has been compromised by rising populations, changing climate, and increased development pressures. In the absence of the Chesapeake Bay Program, conditions would likely be much, much worse.

Managing nutrient flows from multiple sources isn't easy in a vast and rapidly changing watershed. Just like finding a cure for cancer isn't easy. Or ending poverty. While the Chesapeake Bay (and the Wappinger Creek) aren't as clean as we would like them to be, they would be a whole lot worse in the absence of watershed science and management programs.

As we reflect on Watershed Awareness Month, let's feel good about our accomplishments. But let's also commit ourselves to the great challenges that remain. Humans need healthy aquatic ecosystems, pure and simple. We need to keep moving science-based ecosystem management forward, even if it can feel like we are working against the tide. There is just too much to lose.