Originally posted on Brink News July 4, 2022.

In recent years, a series of papers in academic literature has attempted to quantify the potential for “natural climate solutions” (NCS) to offset global emissions of greenhouse gases.

The papers identify a wide range of natural processes that either remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere or reduce the emissions of CO2, methane and/or nitrous oxides from forests, wetlands, and agriculture. The papers have been widely reported on in the media and have created expectations among policy-makers and the public that these natural climate solutions have to be an important component of U.S. climate mitigation.

Back of the Envelope Calculations

But the analyses are essentially very elaborate sets of back-of-the-envelope calculations designed as thought experiments. More critically, the analyses are divorced from the myriad social, economic and political contexts that would ultimately determine whether the potential offsets could be achieved.

In effect, the papers do not attempt to address the types of policies that would be needed, but instead assume that simple market forces will prevail and that as the marginal cost of abatement of greenhouse gas emissions increases, use of the varied offset mechanisms will increase.

The most recent global carbon budgets estimate that almost 30% of emissions of carbon from fossil fuels and industry are removed via net uptake by oceans. The magnitude of the net carbon sink on land is more uncertain but could be as much as 20% of fossil fuel emissions and largely reflects the balance of deforestation versus forest regrowth.

Forests are the single largest source of current offsets to U.S. greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The nation’s forests offset 11% of U.S. GHG emissions in 2018, equivalent to 753 million metric tons (MMT) of CO2, based on U.S. Forest Service inventory data. Eighty percent of that occurred in eastern forests — the remainder was in forests along the Pacific coast. Forests in the intermountain west are a net source of carbon emissions because of the devastating effects of fire and insect outbreaks.

It is widely assumed that emission reductions alone will not meet climate mitigation goals, and that significant new sinks for carbon will be required to address the climate crisis. The most widely cited analysis for the U.S. concludes that a suite of 21 different natural climate solutions could provide a theoretical maximum of 1.2 billion metric tons of CO2 equivalents per year of additional mitigation. This would equal over 20% of the country’s net emissions in 2016. The authors note, however, that only a quarter of these emission reductions would be achieved at current carbon market prices of roughly $10 per ton.

Reforestation and Forest Management Are Likely to Disappoint

The NCS analyses conclude that reforestation and “natural forest management” represent the greatest natural opportunities for additional U.S. climate mitigation and could provide over 481 MMT of new offsets per year at a marginal abatement cost of $50/ton. But to understand the challenges, you need to read the fine print. Just over half of the new offsets would be achieved by reforesting 155 million acres of land.

This would require increasing America’s total forestland area by 20%, when U.S. forestland has not increased at all in the last 30 years — and in fact declined slightly between 2000 and 2019.

There is little question that there are compelling reasons to promote reforestation in many regions of the country, but a far bigger challenge is addressing the myriad threats to maintaining the health and productivity of our current forests.

It’s important to note that the estimate of land available for reforestation includes ecosystems that were historically savannas, woodlands and forest/grassland mosaics. The lead authors on several of the NCS papers work for conservation organizations. It seems more than passing strange that they would blithely propose that these ecosystems be converted to closed forests, with such different habitat and conservation values.

The other half of the NCS potential from U.S. forests is from “natural forest management.”

The “management” in this case is achieved by halting all harvests on all of the over 300 million acres of privately owned “mixed native species forests” in the country for the next 25 years, before being allowed to resume at previous levels. This would include basically all forestland in the eastern U.S., other than southern pine plantations.

Neither investor-owned forests nor family forest owners are viable candidates for generating truly additional and permanent forest carbon sequestration

The analysis assumes that harvests from new plantations on reforested lands, plus thinning operations for fire management in western forests, will make up the difference in supply of forest products. The analysis ignores the resulting differences in quality and types of timber harvested, and assumes that this substitution can happen seamlessly in time and space. This goes beyond being simply academic and into the realm of absurdity.

Forest Carbon Offset Markets Are Not Being Properly Regulated

The sale of forest carbon offset credits on both the voluntary and compliance markets is expected to increase dramatically in the next decade.

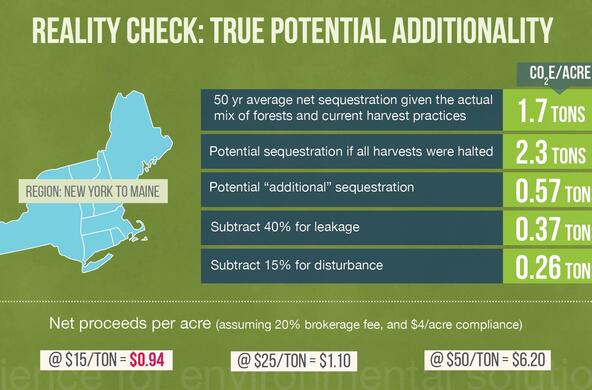

Those markets, at least in principle, represent a pathway to implement natural climate solutions. In practice, there are deep and structural flaws in the protocols that govern those markets, and those flaws routinely allow gross over-estimation of the magnitude of the truly additional carbon offset by the deals. The flaws have been widely reported on in the media and have recently been acknowledged by forest landowners who have sold the credits.

American forestland has bifurcated into the fraction that is investor-owned and intensively harvested, and a larger fraction that is family owned or publicly owned and very lightly logged (if at all). Ignoring these differences misrepresents the opportunities for truly additional offsets in both cases.

In fact, neither investor-owned forests nor family forest owners are viable candidates for generating truly additional and permanent forest carbon sequestration. Offset prices would need to be dramatically higher to lead to reduced harvest rates on the corporate lands, and at that point, leakage would almost certainly displace harvests to other lands (and likely offshore), wiping out most of the offsets.

And while family forest owners (and public land managers) would likely welcome the grossly exaggerated payments that offset deals can generate, their lands are already sequestering carbon at near maximal rates. When questioned by reporters, these landowners and public land managers are quick to point out that they have no intention of changing their management, thus eliminating any basis for meeting the “additionality” requirement for any legitimate claim for new offset credits.

The bottom line is clear — a great deal of money will change hands, landowners with large tracts of forestland will be enriched, companies will claim grossly exaggerated quantities of carbon offsets, and brokers will collect large fees. There is no credible argument that current protocols on either the compliance or voluntary carbon markets will generate any meaningful increase in carbon sequestration in U.S. forests. And in the meantime, the purchase of offset credits will allow continued emissions of not just carbon but other pollutants, with disproportionate impacts on disadvantaged communities.