1. Introduction

Worldwide, more than 1.3 million people die each year of infectious diseases transmitted by a vector, such as a mosquito, sand fly or tick (World Health Organization 2004). Vector-borne diseases also inflict heavy tolls on crops, livestock and wildlife (Daszak et al. 2000; Anderson et al. 2004). As a consequence, understanding variation in exposure risk to vector-borne diseases, and managing environments to reduce this risk, are important goals.

Vector abundance is a key determinant of risk of exposure to the pathogens that vectors transmit (Ginsberg 1993; Antonovics et al. 1995; Mather et al. 1996). The abundance of vectors can be determined by climate-driven population performance (Fish 1993; Randolph 1993; Martens et al. 1995; Lindgren et al. 2000; Rogers & Randolph 2000; Yang et al. 2008). Climate can regulate the abundance of arthropod vectors directly, e.g. by desiccation, freezing or overheating, or indirectly, e.g. by altering vegetation type and structure. However, despite some clear cases in which climate regulates vector abundance (Alto & Juliano 2001; Afrane et al. 2005, 2006; Yang et al. 2008), in many other cases climate fails to explain vector abundance or disease incidence (Reiter 2001; Schulze & Jordan 2005; Ostfeld et al. 2006). For example, long-term population dynamics of blacklegged ticks (Ixodes scapularis) in New York, USA were not associated with temperature (growing degree-days) or precipitation parameters (Ostfeld et al. 2006). Alternatively, abundance of vectors that are host- or habitat-specialists can be regulated by the availability of specific hosts (e.g. fleas on prairie dogs; Gage & Kosoy 2005) or breeding sites (e.g. tree-hole mosquitoes; Juliano 2007). However, most vectors of zoonotic pathogens are host- and habitat-generalists, that is, they feed on a variety of host species and occupy different habitat types (Ostfeld & Keesing 2000; Molyneux 2003). For these species, vector survival and abundance might depend most strongly on the community of host species upon which they feed.

Host species can differ dramatically in their quality as a reservoir, that is, in their probability of infecting a feeding vector with a specific pathogen (Ostfeld & Keesing 2000 for review; Komar et al. 2002, 2003; LoGiudice et al. 2003). However, host species might also differ substantially in their quality as a host, here defined as the probability that a vector attempting a blood meal from that host successfully feeds and survives. Previous studies have documented that host quality does vary. For example, Ogden et al. (2004) found that adult female I. scapularis ticks that fed on raccoons had significantly shorter pre-oviposition periods than did ticks that fed on dogs. And Randolph (1979) showed that Ixodes tranguliceps ticks that fed on Apodemus sylvaticus were more likely to become engorged than were ticks that fed on laboratory mice when the hosts were repeatedly reinfested with ticks. Variation in host quality appears to be caused by differences in either host-immune response (Randolph 1979) or host grooming (Ostfeld & Lewis 1999; Shaw et al. 2003). If some host species that are abundantly parasitized in nature are of sufficiently low quality that they strongly reduce tick fitness compared with other hosts, then those poor quality hosts might act as ecological traps (Robertson & Hutto 2006).

Whenever host species differ strongly in host quality, the abundance of a generalist vector could be limited by the relative availabilities of the species comprising the host community—i.e. by the composition of the host community. Communities with a high proportion of poor-quality hosts would then be expected to produce smaller populations of vectors.

We investigated whether the identity of hosts determines survival of blacklegged ticks, which are vectors of Lyme disease (LD), granulocytic anaplasmosis and babesiosis, three widespread and emerging diseases in the US and Europe. LD, the most prevalent of the three and the best understood, is caused by a spirochete bacterium, Borrelia burdorferi, which is passed from one host to the other by the bite of an infected ixodid tick. In the northeastern and mid-western US and eastern Canada, the vector is the blacklegged tick, I. scapularis. Larval ticks feed on a wide variety of vertebrate hosts, including mammals, reptiles and birds (Keirans et al. 1996). Within LD endemic zones of the northeastern US, larval ticks commonly feed on at least 15 species of forest mammals and ground-dwelling birds (LoGiudice et al. 2003). Larvae that feed successfully molt into the nymphal stage, which overwinters before seeking a host the following late spring or early summer. The population density of nymphal ticks, and that of infected nymphal ticks, are key ecological risk factors in the LD epidemic (Lane et al. 1991; Barbour & Fish 1993; Ostfeld & Keesing 2000).

To determine if the composition of the host community could affect tick survival, we experimentally determined the proportion of ticks that fed successfully on each of six host species. Then we combined these results with data on tick burdens and reservoir competence of hosts to parameterize a model for how the loss of host species, alone or in combination, from ecological communities would affect the density of infected nymphal ticks (DIN).

2. Material and methods

(a) Capturing and holding hosts

In August and early September 2008, during the peak of the questing period for larval ticks, we captured six commonly parasitized species of hosts at our forested field sites at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, New York. Hosts were white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus), eastern chipmunks (Tamias striatus), grey squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis), opossums (Didelphis virginiana), veeries (Catharus fuscescens) and catbirds (Dumetella carolinensis). Details of the trapping procedures are available as electronic supplementary material. After capture, animals were transported to the Rearing Facility at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies. Animals were then placed in appropriately sized cages (details in electronic supplementary material), and supplied with food and water ad libitum. All cages had floors of wire mesh or parallel wires. These cages were held over dishpans containing layers of moistened paper towels, with a border of petroleum jelly placed around the interior of the pan to prevent ticks from climbing out (Sonenshine 1993). Paper towels were examined exhaustively every 24 h to count all ticks that had dropped off the host. Hosts were kept under these conditions for 72 h, which was long enough for most larval ticks to feed to repletion. There were no differences among host species in the rates at which ticks fed (figure 1 in the electronic supplementary material).

(b) Reinfesting hosts

After the 72 h pre-test period, each host was inoculated with 100 larval ticks that had been either collected in the field or hatched from eggs in the laboratory. Larvae hatched from eggs in the laboratory were the offspring of locally collected adult ticks fed on rabbits. Mice and birds were restrained by hand during inoculation; all other hosts were restrained in nylon mesh-handling cones. Inoculations were conducted by placing the 100 ticks, which had been pre-counted and placed in plastic vials, on the host's neck and head with a number 00 paintbrush. Brushes were checked carefully to ensure that no ticks remained on the brush after inoculation. After inoculation, the host was placed in a motion-restricting chamber for 4 h to allow the larvae time to attach without being immediately groomed off. The chambers consisted of appropriately sized PVC pipe (3.2 cm diameter for mice, 5 cm diameter for chipmunks and veeries, 7.6 cm diameter for grey squirrels and grey catbirds, 10 cm diameter for small opossums, and 15.2 cm diameter for larger opossums) with holes drilled through for air circulation. Organdy fabric was used to cover the holes to prevent ticks from leaving the chamber, and the ends of each pipe were tightly capped. Food was placed in each chamber (apple slices for mice, chipmunks, squirrels and opossums; honeysuckle berries for birds) as a source of food and moisture during their restraint.

Hosts were then returned to their individual cages, which were suspended over pans of moist paper towels for collecting ticks. We did not attempt to control for prior exposure of hosts to feeding ticks, which potentially can affect subsequent tick feeding success (Levin & Fish 1998, but see Hazler & Ostfeld 1995), but because they were mature animals captured months after the beginning of the tick season at our sites, all hosts had prior experience with ticks. The number of larval ticks that fed from each individual host was determined by counting ticks that dropped into pans every 24 h for 96 h following inoculation. We held animals for 96 h post-inoculation because data from these host species indicated that few ticks remained on hosts after 4 days, and this value did not vary among species (figure 1 in the electronic supplementary material). Hosts were returned to their points of capture after tick collection was complete.

We categorized the original 100 ticks as replete; partially fed; chewed; and unfed (flat). Any ticks not accounted for directly were assumed to have been consumed or destroyed during grooming (Shaw et al. 2003). The number of larvae feeding to repletion (full or partial) was compared using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with host species as the treatment and individual hosts as replicates.

(c) Building and parameterizing the model

To quantify the impact on LD risk of host-specific vector survival rates, we adapted a previous model developed to quantify the impacts of host species on the proportion of infected nymphal ticks (Giardina et al. 2000; LoGiudice et al. 2003). Our model, which calculates the density of infected nymphal ticks, incorporates host-specific variation in observed tick burdens, tick survival rates, population density and reservoir competence. The DIN, which is the primary risk factor for LD is,

Parameter values, sample sizes and sources for feeding success, body burden of larval ticks, number of ticks trapped by each host (see main text), reservoir competence and density. (O, original data.)

(d) Removing hosts

We calculated DIN for a host community consisting of six species, and then removed each species individually to determine its specific impact on DIN. When a species was removed from our model, we calculated the number of larval ticks that that species would have ‘trapped’ as Bi/Si, where Si is the proportion of larval ticks that successfully feed on host i, as determined by our laboratory reinfestation experiment. The number trapped is the number of questing larval ticks that would be added to the system if host species i were removed; this number is the product of the proportion of ticks that feed successfully on each individual and the mean number of individuals of each species. To account for this increase in questing larval ticks, we then redistributed those larvae on the remaining host population in proportion to the percentage of the total tick population that each host, j, was already feeding:

Because vertebrate host species do not appear to be lost from ecological communities at random, we also used our model to simulate the sequential loss of more than one species in an order determined by empirical observations of fragmented forest habitats (Ostfeld & LoGiudice 2003). The sequence of host removal was determined by a combination of observations from 40 forest fragments in the northeastern United States (LoGiudice et al. 2008) and observations of forest fragments in mid-western North America (Rosenblatt et al. 1999; Nupp & Swihart 2000; LoGiudice et al. 2003; Ostfeld & LoGiudice 2003). Veeries, which prefer forest interiors, were removed first, followed by opossums, which are medium-sized mammals that require home ranges larger than many forest fragments, and then squirrels, chipmunks and catbirds. Mice were present in all runs of the model, reflecting results from forest fragments of the northeastern USA (LoGiudice et al. 2008).

3. Results

(a) Reinfestation experiment

When hosts were experimentally inoculated with ticks in our experiment, most ticks stayed on the hosts to attempt to feed; fewer than 10 per cent dropped off in the apparatus. When ticks did drop off, however, there was no significant difference in the percentage that dropped off each host species (ANOVA on ranks, p = 0.21; figure 2 in the electronic supplementary material).

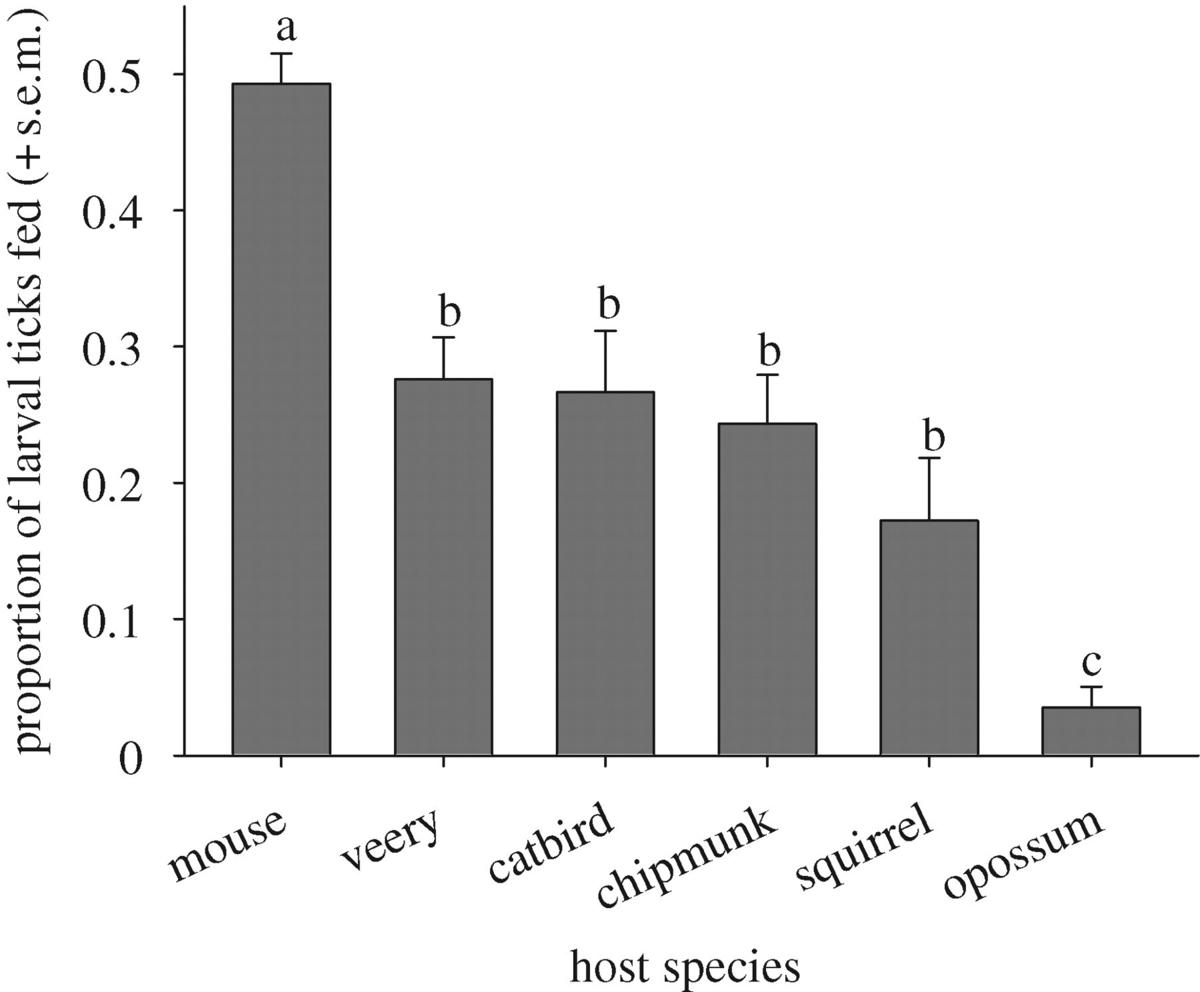

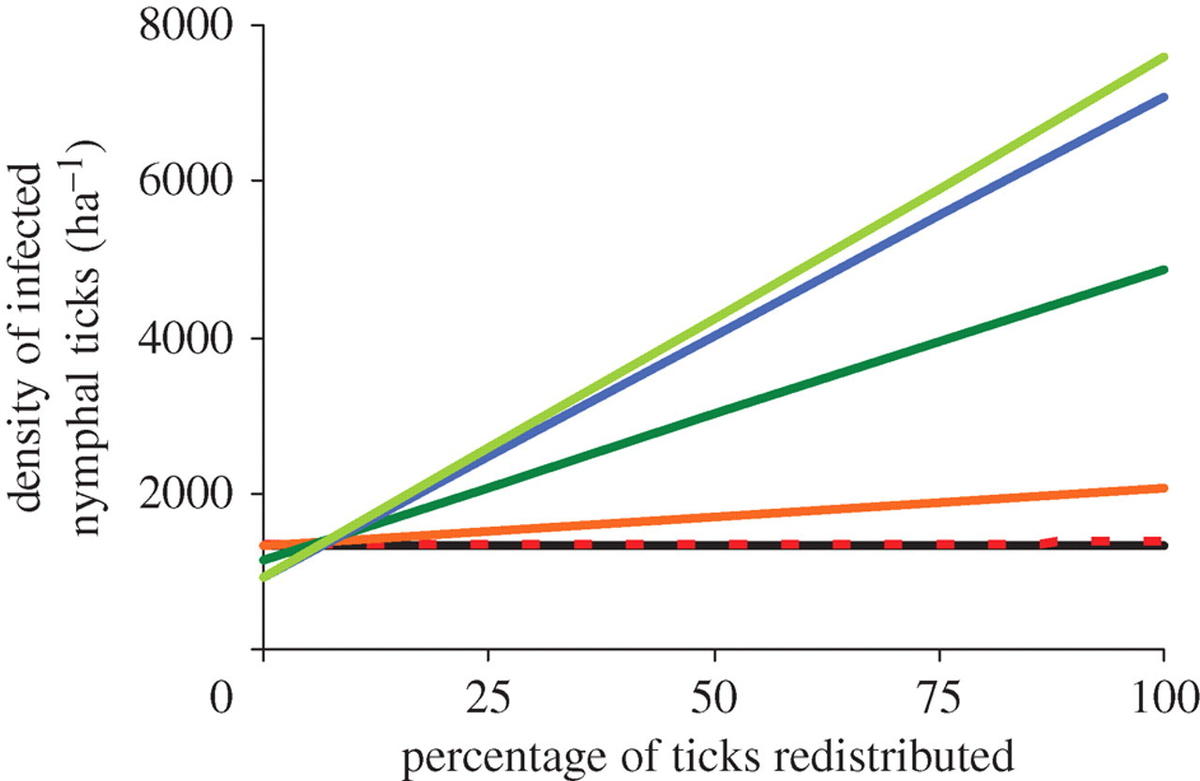

Species varied significantly in their quality as hosts for ticks (p < 0.05). Almost half of the larval ticks that were placed on white-footed mice fed to repletion, while only 3.5 per cent of ticks that fed on opossums did (figure 1). Eastern chipmunks, grey squirrels and the two species of birds—veeries and catbirds—were of intermediate quality. A small percentage of ticks were recovered unfed or partially engorged (table 1 in the electronic supplementary material). The remaining ticks were not recovered from their vertebrate hosts or from the apparatus that housed the hosts, indicating that they had been consumed during self-grooming.

These host-specific differences in feeding success became more pronounced when we took into account natural tick burdens. At our upstate New York sites, an average of 199 ± 90 (mean ± s.e.) replete larval ticks are collected from opossums caught in the wild during the larval activity peak (updated from LoGiudice et al. 2003 with data from the current study). But these larvae represent the 3.5 per cent that feed on opossums and survive—the vast majority (96.5%) of larval ticks that encounter an opossum and attempt to feed are apparently consumed. Working backwards, during any given week in the larval activity peak, each opossum must host more than 5500 larval ticks to produce 199 that successfully feed. By this logic, during the larval peak, each mouse encounters approximately 50 larval ticks per week, almost half of which feed to repletion and become nymphs. Thus, opossums in the host community serve as ecological traps for larval ticks, concentrating large numbers of larvae and then consuming them before they can feed and molt into nymphs (table 1).

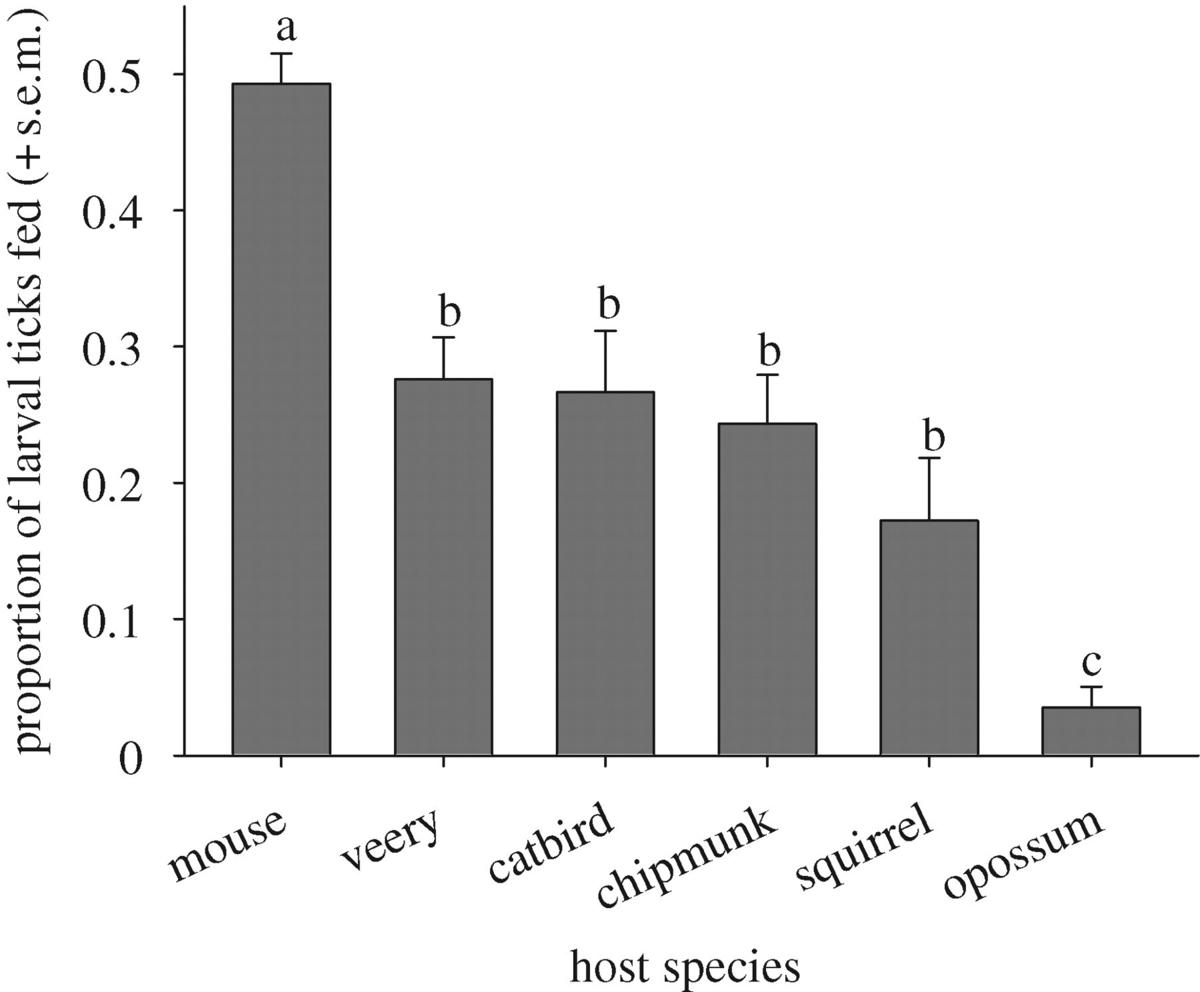

(b) Removing hosts

The effect of removing individual host species was highly species-specific (figure 2). Removing mice, for example, always resulted in a substantial reduction in the density of infected nymphs, whereas the effect of removing squirrels could either modestly decrease or substantially increase DIN depending on the degree to which ticks were redistributed among the remaining hosts. If 33 per cent of ticks were redistributed, the loss of a single opossum (table 1) resulted in a 15 per cent increase in LD risk (figure 2). Greater rates of redistribution resulted in considerably higher DIN values.

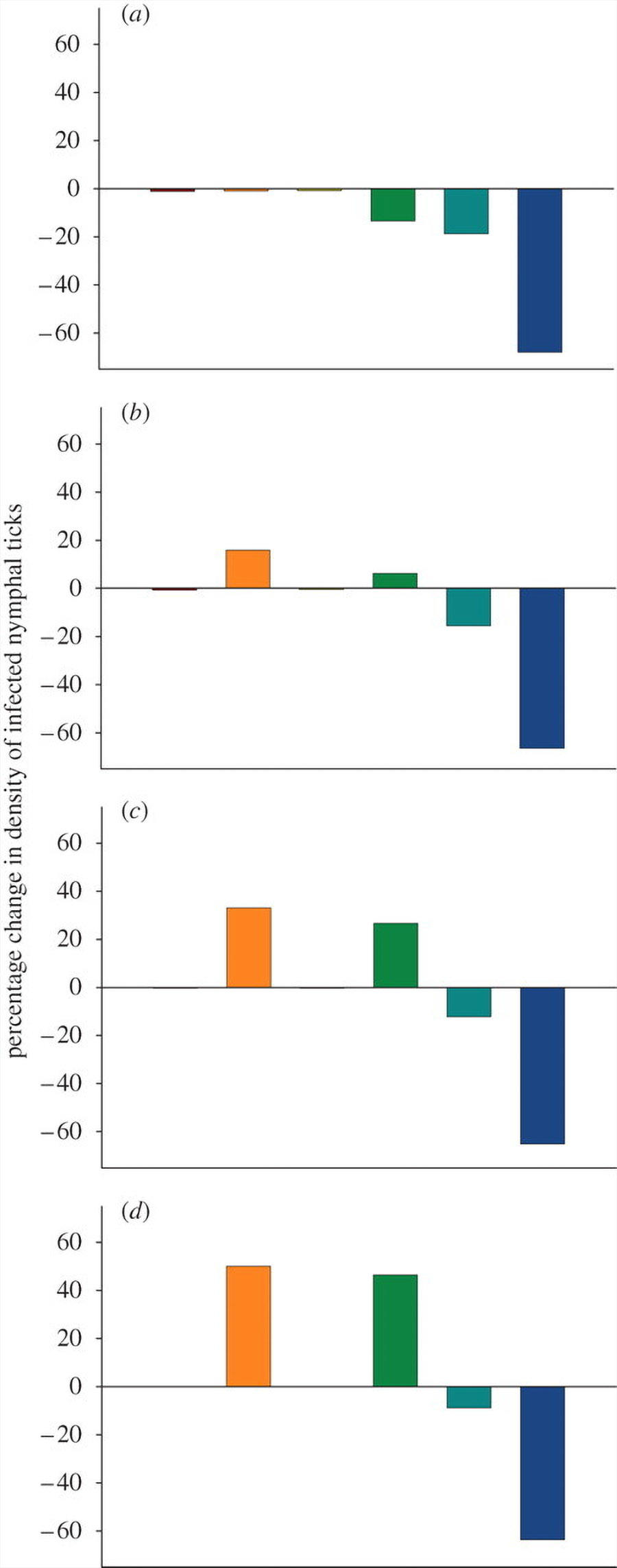

When we removed more than one host species from the community, the DIN increased as more host species were removed. This result was obtained whenever more than 10 per cent of ticks that would have fed on missing hosts were redistributed on remaining hosts (figure 3).

4. Discussion

The species identity of a host encountered by an unfed larval tick had a significant effect on the probability of tick survival. In our experiment, larval ticks that attempted to feed on white-footed mice were an order of magnitude more likely to survive than were ticks that attempted to feed on opossums. These results, combined with data on host abundance, natural tick burdens and reservoir competence, revealed that the effect of hosts on the DIN is highly species-specific. The removal of mice from a simulated community always reduced DIN while the removal of opossums increased DIN if the ticks that would have fed on the opossum were redistributed onto the remaining hosts. When species were removed sequentially in an order observed in field studies from the eastern United States, DIN increased as more species were lost from the community of hosts if the ticks that would have fed on the removed hosts were redistributed.

Our study design involved treating all hosts identically to minimize the potential for laboratory artefacts to produce interspecific differences. However, we were unable to control for all potential biases that could have affected results. For example, prior exposure to ticks can reduce tick feeding success (Randolph 1979). We did not directly account for species-specific differences in prior exposure, but all hosts in our experiment had been heavily infested with ticks prior to our experiments (table 1). Immune responses that directly kill ticks would have resulted in the recovery of differential numbers of unfed ticks in the apparatus, which did not occur (table 2 in the electronic supplementary material). However, the differences in grooming efficacy that we observed might have been the result of species-specific differences in immune responses such as inflammation, which can stimulate or intensify grooming. Our initial restraint of the hosts in the laboratory might have biased our results if some host species are better able to groom off ticks upon encounter rather than later, after they attach. However, the reverse bias could have arisen if we had not restrained the hosts upon infestation.

Our model was parameterized almost entirely using data from our study site. As described in §2 and table 1, we used literature values to estimate the densities of opossums and grey squirrels. Density estimates for both of these species vary somewhat depending on location and methods, so we chose conservative estimates. For example, opossum densities in oak-hickory forest range from 0.9 to 2.5 per hectare; in this study and elsewhere (LoGiudice et al. 2003), we used 1 opossum ha−1 to parameterize the model. Our model results are insensitive to variation in host density within the range described in the literature (LoGiudice et al. 2003). Similarly, we used a sequence of species loss that combines data from our study sites with data from other published studies. This sequence should be considered provisional until better information on community disassembly rules becomes available (Ostfeld & LoGiudice 2003). However, data from 40 northeastern USA forest fragments confirm that white-footed mice are the only host species present at all sites (LoGiudice et al. 2008), from species-poor to species-rich. In such situations, the end result of species loss is that disease risk is highly elevated in habitats with the lowest host diversity.

The results of our model suggest that the loss of host species from an ecological community could increase LD risk if the ticks that would have fed on the lost species redistribute to the remaining hosts. Recent evidence demonstrates that decreases in the abundance of a specific host do cause substantial increases in the tick burdens on remaining hosts (Brunner & Ostfeld 2008), suggesting that redistribution in nature is substantial. Twelve years of data on six trapping grids in Dutchess County, NY, showed that as chipmunk density declined from 40 to 0, the number of ticks on mice increased by 15 larvae per mouse, an increase of approximately 50 per cent. Many important questions about redistribution remain to be resolved, including the degree to which redistribution of tick meals occurs across species and the key factors that cause temporal and spatial variation in redistribution.

In a recent synthesis, Robertson & Hutto (2006) define an ‘ecological trap’ as a habitat that an organism preferentially occupies and in which it has lower fitness than it would in an alternative available habitat. They define three criteria for identifying a trap. First, the organism must show a preference for that habitat. Second, fitness must vary among habitats. And third, the organism must have equal or lower fitness in the preferred habitat compared with alternative habitats. In our study, we determined conclusively that the survival of the ticks varies among host species, which can be considered habitats. We also showed that fitness is lower for ticks on opossums and squirrels than on alternative host species like mice. The question of preference is harder to characterize in this system. The mean number of successful tick meals on individual opossums (199) and squirrels (145) is five to eight times greater than the number on individual mice (25). Our calculations indicate that attempted meals on opossums exceeded those on mice by two orders of magnitude (table 1). These data suggest that ticks might prefer opossums and squirrels over mice, although true preferences are difficult to assess without controlled assessments of host choice. Opossums and squirrels seem to meet the criteria of ecological traps as described by Robertson & Hutto (2006).

Given the high mortality of ticks on opossums and squirrels, one might expect ticks to evolve the ability to detect and avoid feeding upon these hosts. In this case, inoculating these hosts with ticks might overestimate true mortality rates in nature. Two lines of evidence suggest that this is not the case. The first is the sheer number of larval ticks that feed to repletion on these hosts, as described above. The second is the number of ticks recovered from the apparatus used to inoculate the hosts with ticks. Ticks placed on hosts were not more likely to drop-off of opossums or squirrels than off of mice or any other species. Ticks might fail to drop-off low-quality hosts because they cannot detect host quality. Evidence indicates that larval ticks can discriminate only modestly among hosts (Shaw et al. 2003), though this issue has not been thoroughly investigated. Another possible explanation is that the daily mortality rate while larvae are questing for hosts is sufficiently high that attempting to feed on any host leads to a higher probability of survival than does waiting to encounter an optimal host. High seasonal attrition rates in densities of questing larvae suggest that field mortality may be high (Fish 1993; Ostfeld et al. 1996), supporting this hypothesis.

Opossums and squirrels played large roles in determining DIN in our model for several reasons. First, they trap large numbers of larval ticks, as our experiment revealed. Both species are also relatively poor reservoirs for B. burgdorferi, with opossums and squirrels infecting, respectively, only 3 per cent and 15 per cent of ticks that feed successfully (table 1). Indeed, we found a significant positive correlation between the quality of our six species as hosts for vectors, measured as the proportion of larvae that successfully feed to repletion, and their competence as reservoirs, measured as the proportion of successfully feeding ticks that become infected with the pathogen (R = 0.85, p = 0.03). Further investigation will determine whether this relationship holds for other species in the LD system and whether a similar relationship occurs in other vector-borne disease systems.

One ecological feature that might make white-footed mice an optimal host for both vectors and pathogens is their ubiquity (Ostfeld & Keesing 2000). A recent study of 40 forest fragments in the northeastern US found that mice were the only vertebrate species occurring in all fragments (LoGiudice et al. 2008). The order in which species are lost is harder to predict (Ostfeld & LoGiudice 2003). Multiple lines of evidence suggest that larger mammals are among the first species to disappear as forest fragments become smaller and, consequently, as diversity declines (Rosenblatt et al. 1999; Ostfeld & LoGiudice 2003; LoGiudice et al. 2008). Consistent with these results, a previous study demonstrated a negative relationship between forest fragment size and several measures of LD risk (Allan et al. 2003). Presumably, the smallest fragments had a predominance of white-footed mice, which caused an increase in both tick infection prevalence and the density of infected ticks. But the study did not provide evidence for specific mechanisms. Our results suggest that smaller fragments may have lost species that regulate vector abundance, a mechanism that has been proposed (Keesing et al. 2006) but never demonstrated to reduce disease risk.

As species are lost from a community, the ticks that would have fed on them may (or may not) redistribute themselves on other hosts. Given that larval blacklegged ticks are extreme host-generalists (Keirans et al. 1996; LoGiudice et al. 2003), we expect such redistribution to accompany species losses. Our model incorporates this effect. It does not, however, incorporate changes in the abundance of the remaining host species, as might occur if a competitor or predator was removed. For example, the loss of chipmunks could result in increases in the abundance of mice, because mice and chipmunks are both small, granivorous rodents that compete for food resources. If the density of remaining hosts increases as diversity declines, increases in LD risk with species loss would be even greater than predicted by our model.

A number of studies have now shown that diversity reduces disease risk for both vector-borne and non-vector-borne diseases, including West Nile virus encephalitis (Ezenwa et al. 2006, 2007; Swaddle & Calos 2008; Allan et al. 2009), bartonellosis (Telfer et al. 2005), schistosomiasis (Johnson et al. 2009) and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (Mills 2005; Suzán et al. 2009). But an understanding of the mechanisms behind this phenomenon has lagged behind and been controversial (Keesing et al. 2006; Begon 2008; Salkeld et al. 2008). This study demonstrates a specific mechanism—a reduction in vector abundance—by which diversity can reduce disease risk. Our results suggest that maintenance of species that serve as ecological traps may be an important component of management efforts to mitigate vector-borne disease transmission.

Acknowledgements

All procedures were conducted with approval from the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

This work was funded by grants from the