Karen Roy was in grad school in the early 1980s when two things made her realize acid rain was a big deal. The first was the decline of the forest on Camel’s Hump, a mountain in Vermont. The second was learning about dying lakes in the Northeast.

“There were people talking about the record fish that were no longer found,” she says.

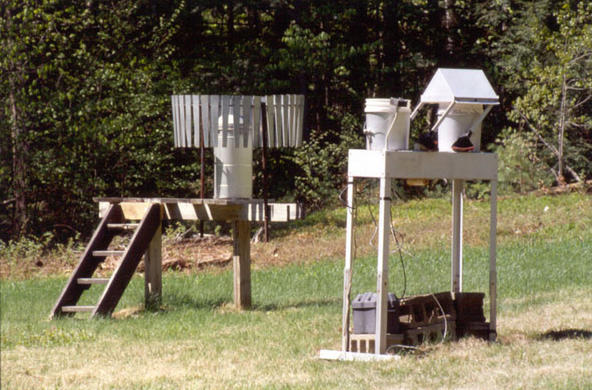

Roy now manages the Adirondack Long Term Monitoring program. When I visited, she and her team were heading to a pond near Lake Placid, New York. They were going to check how acidic the water is these days; a process repeated in dozens of lakes monthly. But first we have to hike through a forest.

“What affects the forests, ultimately affects lakes and streams as well,” Roy says.

Forests and lakes are connected, but how they recover from acid rain is very different.

Since the bad old days of the 1970s and '80s, there has been a whole lot less acid falling on the Northeast. That’s mostly thanks to the 1990 Clean Air Act, which has made a big difference to lakes and streams. Many are now coming back to life, with fish and other fauna reviving. But that’s not the whole story.

“It’s just like everyone [said], 'Whew, that problem is solved, now we can think about something else,'” says Gene Likens, co-founder of the Cary Institute of Ecosystems Studies, and one of the first people to discover acid rain in the U.S.

He says forests are having a much tougher time. Years of acid rain falling on their soils has leached away calcium and other minerals that used to neutralize the acid. So, even though today’s rain is far less acidic, sensitive forests are less able to deal with it.

“The system is more sensitive. And one could argue that the impact is as bad as it was in 1990 when we passed the Clean Air Act amendments,” he says.

Trees like sugar maple and red spruce are suffering the most. They need a lot of calcium and the soils are depleted. Forests are on a completely different timeline than lakes.

“Some will recover on the order of decades. But others will not recover for many, many, many decades,” says Charles Driscoll, university professor of environmental systems engineering at Syracuse University.

That’s why, despite all the progress made since 1990, Likens and Driscoll would like to see lawmakers reduce smokestack emissions even more.

That’s unlikely. The political environment has changed so much since the 1990 Clean Air Act was passed with bipartisan support. That bill included the acid rain provisions, the first widescale use of cap and trade.

Back then, cap and trade was an idea nearly everyone could get behind. Democrats and environmentalists liked that it could slash pollution. Republicans liked that it used market forces and gave industry choices.

“What had been for decades a bipartisan issue has evolved into what is now a highly polarized, partisan issue,” says Robert Stavins, a Harvard professor who studies emissions trading programs.

The 1990 Clean Air Act was championed by both President George H.W. Bush and northeastern Democrats. The cap and trade program helped cut acid rain-causing sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides by more than 70 percent -- faster and more cheaply than planned.

“It was decidedly a success,” Stavins says.

But critics say it had one flaw.

“Congress never put a provision in there to make changes to the program in the future,” says Gary Hart, owner of Clean Air Markets, and former manager of emissions trading at Southern Company, the large utility.

By the 2000s, the bipartisanship was gone. Democrats killed Republican acid rain proposals because the bills didn’t do what they wanted about climate change. Democrats tried to apply cap and trade to carbon dioxide, which Stavins says led a new breed of Republicans to turn on their own idea, “because it was the mechanism on the table.”

Critics labeled it "cap and tax." Meanwhile, the public became skeptical of markets after the financial crisis.

With no help from Congress, Presidents Bush and Obama started trying to change the acid rain rules through regulation. Hart says that caused more damage.

“When the government comes in and changes the program in the middle of the game, and sort of changes the rules, it really impacts investors and the players in the market. It impacts their confidence,” he says.

Trading in the acid rain cap and trade program has all but ceased.

In the end, regulations for other pollutants like mercury and particulates have had the side effect of reducing acid rain even more. But those regulations are a final blow to one of the most successful examples of using the market to solve an environmental crisis.