A new weapon in the fight against Lyme disease may come not from a pill or an injection, but an idea — preserving a rich array of wildlife.

Studies reveal that the greater the diversity of animal species, the less chance Lyme disease and other tick-borne diseases will spread to people.

The reason? Some animals are better sources of Lyme disease than others. The ones that are better sources — mice in particular — tend to dominate when biodiversity declines. And some species eat more ticks than others.

Such research has potentially huge local implications. Dutchess County consistently has among the highest per-capita rates of Lyme disease in the nation. And in 2011, the county ranked first in the state and 13th nationally in per-capita rates of an emerging, malaria-like threat carried by ticks — babesiosis.

But while evidence of biodiversity's value is mounting, little has been done to generate practical solutions from that information, and rarely is public health mentioned by policymakers as a reason to support biodiversity.

"What we haven't done — and I don't think anybody has done — is take those (research) results and model them on a landscape," said Sacha Spector, director of conservation science for Scenic Hudson, the land trust based in Poughkeepsie. "It would be a powerful tool."

Indeed, at a meeting in New Paltz on Tuesday of more than a dozen local advisers to the state on conserving open space, the need to preserve biodiversity was highlighted in connection with rare turtle populations. But there was no mention of Lyme disease.

Scientists and advocates agree that although biodiversity can be an effective deterrent to disease, it may be one of the hardest to implement.

"I totally agree with (the concept)," said Jill Auerbach, chairwoman of the Hudson Valley Lyme Disease Association. "I don't know how you really effect that in an environment, how you totally change that."

A leading scientist said smart decisions can be made now to preserve open space and to factor the research into future land-use development strategies.

"The issue is, how do we develop intelligently?" said Richard Ostfeld, disease ecologist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook. "I think the science does inform the planning of various kinds of human activities."

Biodiversity

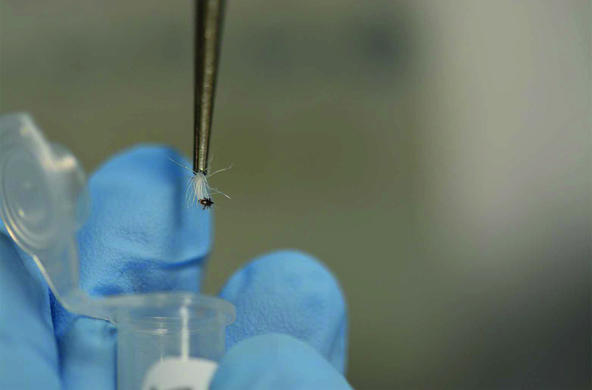

Ostfeld is leading a study that examines larval ticks hatched from eggs laid by adult females whose last meal of blood came from raccoons, opossums or deer.

If you know which animal the mother fed on, so the thinking goes, then you might be able to identify traces of that animal's chemical signature in her babies. Learn that, and then you may be able to identify any tick's last meal just by analyzing its chemical composition.

The study may provide scientists with a new shortcut to understanding how each animal affects the spread of Lyme disease and other tick-borne illnesses. For instance, prior studies have indicated that opossums are one of the best inhibitors of Lyme disease.

Scientists at the Cary Institute have coined the term "dilution effect" to describe how a wider array of species can make it harder for Lyme disease to flourish. Indeed, several recent studies have highlighted the impact biodiversity can have on many infectious diseases.

A study published in the Feb. 13 issue of the scientific journal Nature showed that amphibians have less of a chance of becoming infected by a parasite that causes leg deformities if they live among a broad array of species.

The study examined more than 24,000 amphibians in 345 wetlands in the Bay Area of California. It found that pathogen transmission declined 78 percent in the ponds that had a richer array of species.

In the June 2012 issue of Nature, scientists examined a larger spectrum of plants and animals. The study found that in plants, biodiversity reduced disease in 91 of 107 tests. In animals, biodiversity reduced disease in 31 of 45 tests. Overall, in 80 percent of the cases studied, biodiversity limited the spread of disease.

A study published in December in the journal PLOS Biology used statistical modeling to examine the impact disease has on a country's economic well-being, compared to other factors, such as how effectively the country is governed.

Since most of the poorest and most disease-infected countries lie in the tropics, the authors thought that places that have more wild animals have more potential sources of diseases. But the statistical analysis indicated otherwise.

"Completely to our surprise, it is the opposite effect," said Andrew Dobson, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Princeton University and one of the study's co-authors. "So even though you have more species that might potentially be sources of disease, that source of biodiversity is actually buffering people against disease, rather than amplifying the effect."

The model suggested that if a species-rich country like Indonesia were to lose 15 percent of its biodiversity, the disease burden would increase 30 percent. What it did not answer is why.

Answering that question, Dobson said, "is obviously what we are trying to do next."

Scientists are only beginning to understand the complex reasons why biodiversity can affect infectious disease. Part of the problem is that each disease is unique, and so are the conditions under which it thrives or is held back. The dynamics of Lyme disease involve different conditions and species than, say, West Nile virus.

Tick study

At the Cary Institute, the ongoing tick study would provide scientists with a more efficient way to document the role each species plays in producing infected and noninfected ticks. It would eliminate the need and expense of trapping animals and waiting for the ticks to drop off their hosts, after dying or having their fill of blood, before they can be examined.

"If we can go out into any patch of woods and grab a bunch of ticks and ask what host produced each tick from chemical tracers, we can ask what proportion of the tick population fed from each host," Ostfeld said. "If we know which of the ticks are infected, then we can ask, from which host did each tick get infected. When we determine what proportion of the tick population is infected, we can ask if that's correlated with the diversity of hosts."

Scientists believe certain rodents — mice, shrews and chipmunks — are the best reservoirs for the pathogen that produces Lyme disease. These species don't do a good job of killing the ticks that land on them. And their systems do not fight off the pathogen effectively.

Other species, such as opossums, are more likely to be a dead end for Lyme disease. Opossums are voracious eaters of the ticks that land on them. And when they are bitten by an infected tick, their more robust immune systems appear to do a better job of defeating the disease.

A study published in 2010 in Nature reported that in a typical hectare of woodland in Dutchess County, mice will infect 906 ticks and 78 ticks that bite mice won't be infected. A hectare is equal to 10,000 square meters, or about 2.5 acres. In the same area, opossums infect five ticks and 194 ticks will be uninfected.

Meanwhile, in the same hectare of woodland, nearly 5,500 ticks are killed by opossums compared with about 1,000 that die after landing on a mouse.

"So the takeaway is that opossums kill or fail to infect many scores of ticks, while mice feed and infect scores of ticks," said the paper's lead author, Bard College biology professor Felicia Keesing. "Having mice around increases your risk and having opossums around decreases your risk."

The paper suggests that the species most likely to increase the spread of disease are the ones most likely to be left standing as biodiversity declines.

In the case of Lyme disease, mice can thrive virtually anywhere. The less effective hosts like opossums need larger areas and more pristine habitats.

That dynamic also was apparent in the recently published study of amphibians in California. Species that can colonize quickly tend to disperse and grow quickly, reproduce and die, according to the study's lead author, Pieter Johnson, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Colorado.

Those species "don't allocate — or have — a lot of resources to put into fighting off parasites," Johnson said. "It makes sense if your strategy is to live fast and die young."

In the case of Lyme disease, scientists say their findings suggest there are ways to limit the disease's spread through smart management practices. Keesing and Ostfeld, the Cary Institute disease ecologist, co-authored a study in 2003 that found that the density of infected ticks was three times higher in small forested areas than larger ones.

"One of the most important things we can do is preserve areas that have high biodiversity now and think about how future changes to Dutchess County can maximize biodiversity," Keesing said.

Using the research

Organizations such as Scenic Hudson achieve this by preserving open space through land purchases and conservation easements.

But the notion that public health might be a benefit is rarely leveraged as a reason to support such efforts.

"It's a really important topic and a really hidden part of the equation," said Spector, the conservation science director at Scenic Hudson.

Auerbach, the Hudson Valley Lyme Disease Association chairwoman, agrees Lyme disease is an environmental problem in need of an environmental solution. But she believes research should focus on reducing the number of ticks in other ways, or by finding methods that defeat the insects' ability to transmit the pathogen through bites.

"Until something is done about the ticks, the numbers of ticks and their ability to transmit disease, nothing is going to happen," she said.

One group of Arlington High School science students, inspired by the Poughkeepsie Journal's "No Small Thing" series, is trying to spread the word. Dubbed the Elymenators, the group went before the Town of LaGrange Conservation Advisory Council in December.

"If we are advocating conserving habitat and people know what the root of the problem is, I think progress can be made from that," said Arlington senior Hannah Hart, 17.

It's an uphill battle, says one prominent advocate. Peter Daszak is president of EcoHealth Alliance, a nonprofit based in New York City that was formerly known as Wildlife Trust. The group's motto is "Local conservation, global health."

"You look at Lyme disease, and all the science says that this is a land-use issue, a planning issue," Daszak said. "But when you convert the science into policy, it becomes extremely messy because someone has got to be interested and there has to be a solution that people will buy into or else it just doesn't work."

Maung Htoo, chairman of LaGrange's Conservation Advisory Council, said: "Biodiversity is very important. People don't realize that. People know about Lyme disease. But biodiversity is at a low level (of awareness)."

Ostfeld said there needs to be more research that gives land-use planners specific information to make informed decisions. But that takes money, and most studies that receive federal funding seek to answer broad conceptual issues, Ostfeld said, not specific remedies.

"That is part of the lack of progress," he said. "The major funders are interested in different science than the local end users, and it's a tough nut to crack."