One of America’s hottest cities and one of its coldest may have more in common than you would guess. In places like Phoenix and Minneapolis, scientists think that cities are starting to look alike in ways that have nothing to do with the proliferation of Starbucks, WalMart or T.G.I Fridays. It has to do with the flowers we plant and the fertilizers we use and the choices we make every spring when we emerge from our apartments and homes and descend on local garden centers.

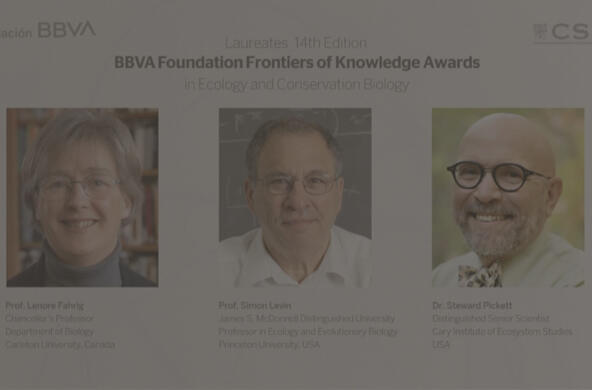

“Americans just have some certain preferences for the way residential settlements ought to look,” Peter Groffman, a microbial ecologist with the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, N.Y., recently told me. Over the course of the last century, we’ve developed those preferences and started applying them to a wide variety of natural landscapes, shifting all places — whether desert, forest or prairie — closer to the norm. Since the 1950s, for example, Phoenix has been remade into a much wetter place that more closely resembles the pond-dotted ecosystem of the Northeast. Sharon Hall, an associate professor in the School of Life Sciences at Arizona State University, said, “The Phoenix metro area contains on the order of 1,000 lakes today, when previously there were none.” Meanwhile, naturally moist Minneapolis is becoming drier as developers fill in wetlands.

In the Twin Cities, scientists have found distinct differences between the plants that grow in urban neighborhoods and those that grow in more rural settings. This doesn’t mean that in one place there are lots of potted geraniums and in another there are native tallgrass prairies. Rather, it turns out that what grows wild in the city is very different from what grows wild just a few miles away. Researchers from the University of Minnesota surveyed 137 yards in Minneapolis and St. Paul, looking at the plants that grew there spontaneously, and found that the yards held more exotic species than rural areas outside the city. Plants that came from much warmer climates were able to thrive there because cities, filled with heat-absorbing buildings and hard surfaces, are warmer than rural areas. They also found that the urban plants were more likely to be able to fertilize themselves, which was important in a place where growing spaces were separated by fences, streets and sidewalks. If you can’t find another member of your species, it’s handy to be able to breed with yourself.

Why does any of this matter to anyone who’s not an urban ecologist? “If 20 percent of urban areas are covered with impervious surfaces,” says Groffman, “then that also means that 80 percent is natural surface.” Whatever is going on in that 80 percent of the country’s urban space — as Groffman puts it, “the natural processes happening in neighborhoods” — has a large, cumulative ecological effect.

Scientists studying the function of urban ecosystems are developing theories of what they refer to as ecological homogenization. Places like Baltimore, Minneapolis and Phoenix appear to be becoming more like one another ecologically than they are like the wild environments around them. Groffman and Hall are currently part of a huge, four-year project financed by the National Science Foundation to compare urban ecology in six major urban centers — Boston, Baltimore, Minneapolis, Miami, Phoenix and Los Angeles. The purpose of the study is to determine how much cities are homogenizing and to create a portrait of the continentwide implications of individual decisions we make about our backyards.

As damaging as urbanization can be to its immediate environs, city living, on the whole, is greener than living in the suburbs. In fact, some ecosystems created by humans might offer us a tool to fight climate change, which brings us back to the Valley of the Sun. According to Hall, the most common “lawn” in Phoenix is what’s called a “xeriscape,” a desertlike environment with native, drought-tolerant plants and rock “mulch.” Superficially, xeriscapes look a lot like the desert that surrounds the city, and they have come to replace many of the green lawns that were kept alive by massive consumption of water. But because xeriscapes are a product of human planning and maintenance, their ecosystems are much different from the surrounding desert.

But different in a better way. Hall and her team found that xeriscapes and the patches of desert preserved as parks within the city store more carbon in their soils than do wild desert. As a result of fertilization and consistent watering, a xeriscape’s soil contains levels of organic materials and plant nutrients that are more similar to what you would find in a lawn than in the desert. That makes a big difference to the microbes that live there, which affect a patch of ground’s carbon-absorbing capabilities.

Homeowner associations, which exist to protect property values in residential communities by enforcing regulations on things like color schemes and holiday decorations, were slow to accept the ecological benefits of xeriscaping, for aesthetic reasons — a house with a well-maintained front lawn means one thing, but we don’t have any associations to make from a front xeriscape, no matter how well maintained. Ecological homogeneity, perhaps not surprisingly, is reinforced by some of the same mechanisms that make our built environment so bland.

As attitudes change, though, it’s possible that xeriscaping could prove to be one instance of human meddling that offers substantial benefits to the environment. Groffman and others think that the ecosystems created within a city like Phoenix might increase the amount of carbon stored in naturally dry places enough that it more than makes up for any decrease caused by development that extends into, say, the forested areas of Minnesota. This isn’t an argument for some kind of carbon-swapping arrangement between the Sun Belt and the rest of the nation, but it does lead to the strange realization that a sprawling metropolis built in a desert might actually offer a path toward something like sustainability.

Ecological Homogenization of Urban America research project »