The work of Cary Institute scientists Dr. David Strayer and Heather Malcom on freshwater mussels received recognition with the November 16 issue of Science Magazine, published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The article “Nearly Buried, Mussels get a helping hand” (November 16, 2012) by Erik Stokstad described how freshwater mussels, of which there are 297 known species, are seriously threatened. He wrote that freshwater mussels “are the most endangered group of organisms in the United States, with most of their river and stream habitats devastated by dams, pollution, and invasive species such as the zebra mussel. Thirty-five species have been declared extinct, others are likely gone, and more than 70 species are teetering on the brink.”

The article described the elaborate collaborative system whereby certain mussel species rely on a certain species of fish to distribute the larvae, a system that could be disrupted by any number of factors, or, as Dr. Stayer’s work showed, by chemical changes due to run-off from agricultural chemicals.

Strategies to culture and restore them have had mixed results.

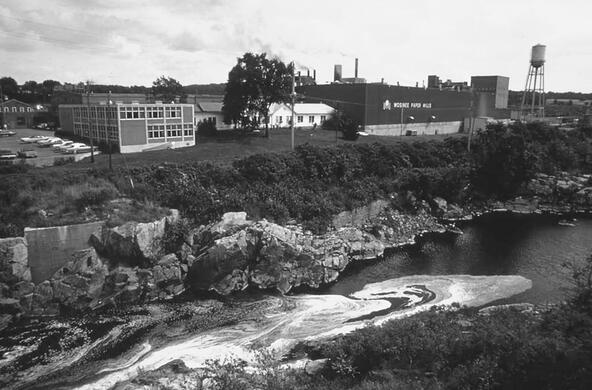

“Just putting mussels back into the stream without fixing the ammonia problem (if ammonia is the problem as we suspect) won’t solve anything, because the juveniles still wouldn’t be able to survive,” explained Dr. Strayer in an interview with the Millbrook Independent. Strayer and Malcolm also published a scientific paper in a technical journal “Ecological Applications” in September of this year which theorizes that ‘recruitment failure’ in freshwater mussel populations is due to excessive concentrations in ammonia and nitrogen associated with fertilizers and other sources especially in agricultural areas.

“People are trying to re-introduce mussels into some streams, as the Science Magazine mentions but there is no point to such programs unless you've first eliminated the problem that killed the mussels in the first place. If ammonia in the sediments is the problem, then simple re-introductions won't do any good. If something else killed the mussels and has now been fixed, then maybe re-introductions would make sense.”

Dr. Strayer was also asked to comment on whether global warming could affect the mussels directly because the streams could get too warm for the mussels in the future. He explained that climate change in the Northeast “could also affect the amount of ammonia in the sediments of the rivers, make it go either up or down, as well as many other aspects of the stream ecosystem. In addition, we expect increases in rainfall and in the frequency of big storms, both of which could have large and far-reaching effects on stream ecosystems. The net effect of all of this is very hard to predict at this point.”

The implications of Dr. Strayer and Heather Malcom’s research are fairly dire for certain mussel species that are prevalent in our streams in Eastern Dutchess.

“Right now, the simplest prediction for the Tenmile basin would be that the eastern elliptio, the subject of our study, and the most common freshwater mussel in our area, will continue to decline, and will disappear entirely in a few decades. Other mussel species with less exacting habitat requirements may persist.

“If our findings are correct, and it's still too early to be sure that we're right, then we can expect to see large, widespread die-offs of mussels in streams that receive a lot of reactive nitrogen from fertilizers, sewage, and atmospheric pollution. This would mean especially mussels in streams near agricultural areas.”