If you’re worried that this year’s mild winter could lead to an explosive tick season, you can breathe a sigh of relief. The harshness of the winter is not predictive of the size of the tick population, experts say.

What can predict this year’s number of black-footed ticks, the variety that’s most likely to give you Lyme disease, is the number of white-footed mice that were around last year — and apparently there were fewer of those pesky little rodents than there were the previous year.

What to expect for the 2020 tick season

With 29 years of data on acorns, white-footed mice, black-legged ticks and Lyme infections in the Hudson River Valley, Richard Ostfeld is pretty sure we’re going to have an average, or even a below average, number of ticks this year.

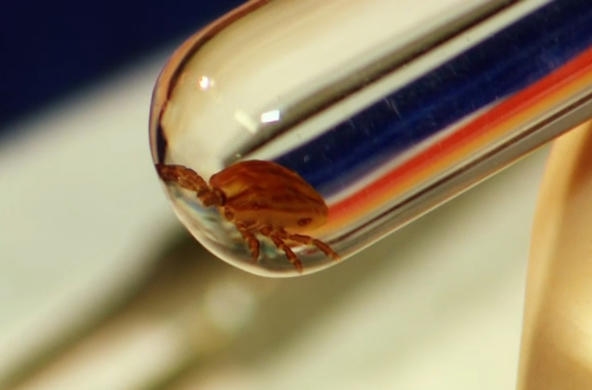

“Baby ticks hatch in August and look for a host,” says Ostfeld, a distinguished senior scientist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, NY. “If they find a white-footed mouse there’s a high probability they will survive and make it into the next stage in the following spring. That’s the dangerous one, the nymph stage, during which the ticks are most likely to infect people with Lyme disease.”

Last year the number of white-footed mice was below average, Ostfeld says. This year, there’s a boom in that rodent population, most likely due to the abundance of acorns last fall, he adds. And that means next year could be the one with an explosion of ticks.

As for the theory that tick populations get knocked back by harsh winters, Ostfeld says the opposite is more likely to be true. “Ticks are pretty impervious to weather conditions,” he says. “And there’s some evidence that they benefit from heavy snow cover, which tends to happen in cold winters. The snow is known to be a good insulation layer.”

The role coronavirus may play

Despite the potential for a lighter tick season, Ostfeld is concerned there could be an increase in Lyme cases because of the COVID-19 pandemic: as increasing numbers of homebound people are spending more time in local parks and in the woods the risk of infections goes up.

“This is kind of a wild card,” Ostfeld says. “Cases could go skyrocketing if people are spending more time in dangerous places. The other thing I’m worried about is that people’s fears of seeing doctors and other healthcare providers may make them less likely to seek help when they are bitten by a tick or develop Lyme symptoms. If they get a case of Lyme disease, it’s not going away on its own and if it goes untreated it can develop into a difficult to treat chronic illness that can be debilitating.”

How to prevent tick bites

For those who are spending more time outside in parks or in their backyards while sheltering at home, it’s important to take precautions, says Alvaro Toledo, an assistant professor of entomology at the Center for Vector Biology at Rutgers University.

“Use repellent,” Toledo says. “Wear long pants so you can protect more surface area and there’s less of a chance of a tick biting you.”

Toledo also advises people to pay attention to where they are walking or running.

“If, for example, you go for a walk, stay in the middle of the trail,” Toledo says. “Don’t go where there are bushes or leaf litter, which are both tick habitats.”

Also, Toledo says, “bear in mind when you are doing work in your own backyard that you may be exposing yourself to ticks. You may think your backyard is a safe place, but when you’re gardening, wear long sleeves and pants.”

Toledo also suggests people keep lawns mowed low to make them less appealing to Lyme-disease-carrying ticks. “And don’t pile wood next to your house,” he adds, “since that will make a perfect nest for rodents.”