Scott Pruitt’s Environmental Protection Agency said Monday that the burning of biomass, such as trees, for energy in many cases will be considered “carbon neutral” by the agency.

“Today’s announcement grants America’s foresters much-needed certainty and clarity with respect to the carbon neutrality of forest biomass,” Pruitt said at an event with forest industry leaders in Georgia.

But the idea that biomass is carbon neutral is contentious among scientists, who fear that forests, once cleared so their wood can be used for energy, may not grow back as planned.

“The big problem is you’re cutting old-growth forests and expecting them to regrow,” said William Schlesinger, president emeritus of the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies and an EPA Science Advisory Board member. “That’s totally unrealistic in 20 years and not guaranteed over 100 years.”

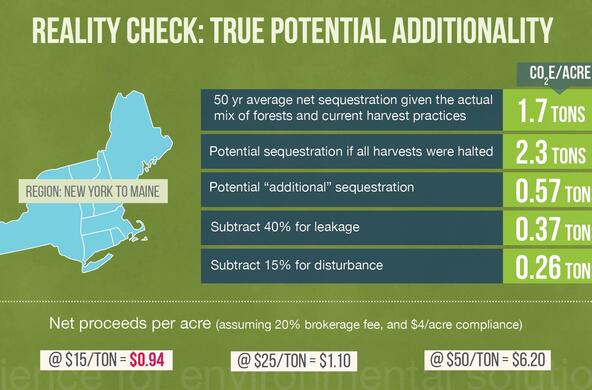

The contention that burning wood for energy is carbon neutral rests on the idea that trees remove carbon from the air as they grow. Therefore, while burning trees releases carbon dioxide emissions, carbon will be pulled out again if the trees grow back. This suggests that burning trees or wood chips can be considered a renewable and sustainable energy source.

But it quickly gets more complicated, which is why the carbon neutrality of biomass has been so hotly debated by some scientists. The EPA’s Science Advisory Board had not completed deliberations on the matter, and the agency’s policy memo released Monday acknowledged that the board had determined in 2012 that “it is not scientifically valid to assume that all biogenic feedstocks are carbon neutral” but that any such determination required further analysis.

While carbon dioxide emissions from the burning of wood go into the air immediately, trees take decades or more to grow back. So if anything happens to interfere with their growth, such as changes made by forest owners based on economics or other factors, the emissions might not actually be removed from the air again.

Yet another consideration arises if wood products are shipped long distances before being burned — for instance, to Europe, which burns a great deal of wood for energy. The energy used for shipping adds to the total greenhouse gas emissions of the process.

Schlesinger said Pruitt undercut the board — which had been “divided on this subject,” he said — with this decision. “There would be no point in doing it now,” he said. “We’re supposed to provide analysis of the basis of decisions. He’s already made the decision. So what’s our role?”

Some forest scientists, however, support the idea that biomass is carbon neutral. More than 100 of them signed a letter to the EPA in 2016 to make that case.

The forest products industry and private forest holders celebrated the EPA announcement. The designation of wood-burning energy as carbon neutral could make it easier for the industry to compete with fossil fuels and bolster its calls for deregulating biomass carbon dioxide emissions so that they are not subject to some provisions in the Clean Air Act.

“Recognizing that forest biomass in the U.S. provides a carbon-neutral source of renewable energy will encourage landowners to replant trees to keep our forests healthy and intact and provide good-paying jobs well into the future,” Dave Tenny, the founding chief executive of the National Alliance of Forest Owners, said in a statement.

Should a new administration revive President Barack Obama’s Clean Power Plan, or something like it, to curb carbon emissions, this new policy means wood energy would be treated like solar and wind power — since in the EPA’s eyes all three are zero-carbon sources of electricity.

Across the Atlantic, European countries are trying to curb carbon emissions to meet promises made under the Paris climate accord, unlike the United States under President Trump. But even there, European Union policymakers have declared wood energy to be carbon neutral. The loophole has led to a flourishing trade in which North American trees are chopped down, compressed into pellets and shipped to Europe to be burned.

Congress, too, has sided with industry. On Monday, the EPA said it was spurred by the May 2017 spending deal, which mandated that the agency, along with the Departments of Energy and Agriculture, make sure their policies “reflect the carbon-neutrality of forest biomass.”

Still, Sami Yassa, a scientist with the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental nonprofit, said the EPA’s announcement Monday is in line with many of the other pro-industry stances Pruitt has taken. “Once again,” Yassa said, “here he’s dismissing established science to give a free pass to his industry pals to pollute.”

Further Reading

Letter to the Senate on carbon neutrality of forest biomass

February 22, 2016