Guide authored by Ava Goodale

Table of Contents

Introduction

The Catskills Region of southeastern New York State provides an unparalleled opportunity for conducting research with local, national, and international relevance. The region is distinguished by a unique mosaic of natural resources within the Catskill Mountains and surrounding watersheds, all of which exist in a socio-ecological system.

This iconic landscape was popularized by Hudson River School painters, literary folk heroes, and tourist destinations, placing the region in the national spotlight and setting a frame around the notion of hinterlands (Stradling, 2010). Similarly, the region’s landmark conservation story gained national attention as it unfolded and was a significant part of shaping our country’s relationship to nature. The aesthetic, recreational, and ecological values of the Catskills Region helped link New York’s identity to its landscape (Stradling, 2010, p. 76). As Stradling noted, “the Catskills should be cherished as a potent inspiration to the student of history, as well as to the poet, the painter, and the writer.”

With this guide, we hope to also include scientific researchers and natural resource managers among those who find inspiration in the Catskills.

The land discussed in this guide is the traditional territory of the Mohawk, Haudenosaunee, Munsee Lenape, Lenni-Lenape, and Mohican, whose ancestors lived in the Catskills Region. As in almost all of North America, colonizers displaced and actively removed indigenous peoples from this landscape, but descendants of the original native communities inhabit this landscape today.

The ecological, social, and land-use history of the Catskills is intertwined with indigenous settlement, and in this guide we seek to acknowledge the role that indigenous peoples have played, and continue to play, in the history of the Catskills. The Native Land Digital Map is a national resource that will help readers better understand the history of these lands. Please see the Human History section of this guide for more information on indigenous peoples of the Catskills.

Purpose

This guide is intended to support individuals and organizations conducting ecological research and environmental monitoring in the Catskills Region of southeastern New York, including portions of Delaware, Greene, Otsego, Schoharie, Sullivan, and Ulster counties.

There are few opportunities for scientists and natural resource managers to exchange information across agencies and institutions, make data freely available for long-term use, and to communicate research findings to the public. To achieve continued conservation success, partnerships are needed between land-use practitioners, academia, and scientists to create evidence-based use guidelines that balance the needs of the industry, tourism, ecological integrity, and resilient landscapes. All stakeholders will benefit from understanding the socio-ecological history of their research area as antecedents to contemporary conditions, diverse perspectives, and future opportunities (NAS, 2020). The purpose of this guide is to provide a resource to facilitate ecological research and monitoring efforts in this important area.

About

The production of this guide was facilitated by the Catskill Science Collaborative (CSC), funded by New York State through Environmental Protection Funds and coordinated by Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies. The CSC carries forward the goals of the Catskill Environmental Research and Monitoring (CERM) group, a collaboration initiated in 2010. These goals include promoting scientific research and environmental monitoring in the Catskills Region on topics relevant to natural resource management, providing a locus of exchange and collaboration opportunities between managers and researchers, developing scientific infrastructure through public databases, and supporting community engagement through public events.

The CSC seeks to improve conservation outcomes by closing the “research-implementation gap,” also known as the “knowing-doing gap,” which can create a mismatch that limits evidence-based strategies and increases inefficient or ineffective decision making (Dubois et al., 2019; Knight et al., 2008; Salafsky et al., 2019).

Why Conduct Research in the Catskills?

Interdisciplinary Research Opportunities

A large number of federal, state, and municipal agencies, universities, and institutes are involved in research, monitoring, and management of Catskills resources. This active and diverse network lends itself to opportunities for interdisciplinary research. The potential for integrated research techniques, multi-institutional perspectives, and cross-disciplinary collaborations is driven by the region’s complex socio-ecological system of historic and contemporary importance. High peaks, remote lakes, unfragmented habitats, networked trails, and tourist hotspots characterize a multi-use landscape ripe with opportunity for interdisciplinary research. Leveraging the many resources of the Catskills and stepping beyond single disciplines allows researchers to address today’s most pressing research questions and diverse stakeholders’ needs.

Long-term Ecological Research

Long-term ecological research has been conducted in the Catskills Region dating back to the 1980s with a general focus on the effect of land-use changes and extractive practices on forest and aquatic ecosystem health. Although understudied in comparison to similar locations, such as the Adirondacks, long-term data sets include stream water quality, acid rain, climate change, nitrogen cycling, forest soils, hillside hydrology, and forest harvesting methods (McHale et al., 2008). For example, streamflow data at Biscuit Brook ranges from 1983-2020 and includes over 3,000 samples (Murdoch et al., 2021). Much of what these long-term data sets and even longer term historic records show is a story of ecological recovery, as the Catskills transitioned in and out of ecological degradation. This storyline will be an especially relevant one in the context of climate change (Robinson, 2007) with the Catskills situated as a climate wildlife migration pathway (McGuire et al., 2016). All told, there is a unique opportunity for today’s researchers to expand upon these historic datasets, understand the interplay among them, conduct meta analyses, and gain new insights from existing data.

Scientific Infrastructure

To help researchers capitalize on these opportunities, the Catskill Science Collaborative (CSC) in conjunction with CERM is developing the scientific infrastructure needed for interdisciplinary and longitudinal research. CERM has played a critical role in bringing together Catskill researchers and managers, identifying the need for greater funding, and articulating a long-term vision to catalyze new research and support the next generation of Catskill scientists and practitioners. This group hosts a bi-annual conference (see 2022 information) to highlight past and current research and monitoring in the region, spur discussion on priority topics, and advance collaborative efforts.

Additional scientific infrastructure includes the CSC data portal, managed in partnership with the Forest Ecosystem Monitoring Cooperative, which is a collection of publicly available data from the Catskills Region. At present there are 25 datasets, ranging in topic from soil chemistry in headwater catchments to forest stand delineation. The data portal helps researchers meet data management plan needs and public access requirements that may increase project funding potential. The CSC also manages a public Zotero bibliography that presently contains over 600 citations from peer-reviewed journals and the gray literature.

An Ecological Primer

The biotic community in the Catskills Region can be viewed as a function of four interacting components: climate, flora and fauna, soils and topography, and the legacy of disturbance (Fahey, 2001). As a primer, this framework will be used to structure a basic introduction to factors influencing the ecology of the region.

Climate

The Catskills are generally characterized by cool summers and cold winters, but significant variations in temperature and precipitation exist due to the rugged terrain of mountainous areas, which range in elevation from 5-1200 meters and feature steep slopes and terraced areas. The average annual air temperature is approximately 41°F with an average annual precipitation of about 63 inches (McHale et al., 2008). Specifically, in the High Peaks area, the mean annual precipitation is 47-60 inches with a January minimum-maximum mean temperature of 9-27 degrees Fahrenheit and a July minimum-maximum mean temperature of 51-72 degrees Fahrenheit. The mean annual frost free days is 90-125 days (Bryce et al, 2010).

The regional climate is changing, as evidenced by the length of the growing season, extreme flooding events, and prolonged droughts. Due to the boreal region to the north and broadleaf deciduous forest to the south, the region is particularly sensitive to these types of ecological changes (Adams and Parisio, 2013). It is predicted that several species will shift their range to expand northward and upslope under different climate change scenarios, leaving the Catskill Mountains as important habitat for vulnerable species. Habitat is predicted to become available in higher elevations of the Catskills for species such as the northern copperhead, northern cricket frog, wood turtle, Kentucky warbler, and cerulean warbler. Maintaining ecological connectivity between the Shawangunk Ridge and the Catskills Mountains will be a key strategy for climate change adaptation (Howard and Schlesinger, 2013).

Flora and Fauna

This heterogeneous landscape includes a mix of land uses, ownership patterns, and unique habitats, such as spruce-fir summits, bogs, beaver meadows, and talus slopes (Van Valkenburgh and Olney, 2004). The Catskills Region is approximately 85% forested, consisting primarily of northern hardwood species (McHale et al., 2008) and in close proximity to the state’s urban centers and sources of pollution to the west and east. Over a dozen vegetation classes have been identified with predominantly mixed oak forests in the lower elevations (< 500m), maple dominated forests at mid-elevations (500-1100m), and fir-spruce at higher elevations (> 1100 m). Shrubs at high elevations include huckleberry, lowbush blueberry, and mountain laurel (Bryce et al., 2010). Stands of eastern hemlock persist in valleys, riparian areas, swamps, and north-facing slopes, despite the legacy of extensive harvest for the tanning industry in the early 19th century. Cathedral Glen on Belleayre Mountain is home to a noteworthy remnant stand (Adams and Parisio, 2013). Although largely a disturbed landscape, first-growth forests remain in significant acreage, totaling approximately 65,000 acres or 6% of the area (Kudish, 2000). Larger tracts of first-growth forest area can be found in Mill Brook Ridge-Big Indian and Slide-Panther-Peekamoose with the remaining acreage fragmented into dozens of smaller patches. The majority of these older forests are found in mountainous areas, averaging 900 meters in elevation with small boreal tree species such as balsam fir, red spruce, mountain ash, and paper birch (NAS, 2020). In sum, these areas represent one of the largest contiguous areas of old growth forest in the United States (Van Valkenburgh et al., 2004).

The Catskill Peaks, located within the Catskill Park, and Ashokan Reservoir Area are designated as Important Bird Areas (IBA). This Catskill Peaks Area is the largest contiguous forest in New York State and contains unique subalpine habitat (Audubon, 2018a). Plateau Mountain and Hunter Mountain’s boreal balsam fir and red spruce habitat host a unique community of endemic birds (Adams and Parisio, 2013). Peaks over 3,000 feet include breeding ground for yellow-bellied flycatchers, Bicknell’s thrush, Swainson’s thrush, magnolia warblers, blackpoll warbler, and more. Peaks over 3,500 feet contain breeding territories for Bicknell’s thrush and blackpoll warblers. These important areas are part of Audubon’s eastern forest priority program (Audubon, 2018a) and monitored by the Mountain Birdwatch program through Vermont Institute of Natural Science. The Ashokan Reservoir Area supports a nesting pair of bald eagles and provides winter grounds for up to six pairs. The reservoir is buffered with undisturbed beech-oak-maple and pine-hemlock forests, which are important stopover habitat for waterfowl, including American black ducks and common loons. For these reasons and more, this site was included in the 2002 Open Space conservation plan as a priority project for New York City Watershed Lands (Audubon, 2018b). High-elevation habitat and associated specialist species are especially vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, as their ability to expand range upslope is physically limited (Adams and Parisio, 2013).

It is also important to note the presence of invasive species in the Catskills, most notably insects and pathogens, such as the spongy moth, hemlock woolly adelgid, and beech bark disease (Lovett et al., 2013). American chestnut was extirpated by a fungal blight and American elm disappeared after the introduction of Dutch elm disease. Red maple and northern red oak generally occupy the niche of these once widespread species (NAS, 2020). Newer invasive species of note include the emerald ash borer, Asian long-horned beetle, and Sirex wood wasp. The Catskills has been one of the hardest hit regions, and the increased presence of these species has changed the forest ecosystem’s structure and function. Impacts include reduced productivity, tree mortality, nutrient cycle disruption, and decreased seed production. Over a longer duration, forest composition and biodiversity are altered. The proximity to urban centers and ecological similarities to Eurasian temperate forests leave the Catskills vulnerable to future establishment of non-native species (Lovett et al., 2013).

Soil and Topography

Due to glacial history in the region, thin soils dominate the landscape with coarse, highly permeable Pleistocene glacial till approximately 1-3 meters thick, which was deposited 10,000-14,000 years ago during the most recent glaciation period (McHale et al., 2008; NAS, 2020). The Pleistocene ice sheets, which created a frozen landscape 20,000 years ago, rounded the high peaks, added glacial sand and gravel to the narrow valleys, and exposed layers of lacustrine clay in certain streambeds as they receded (NAS, 2020).

Soils are classified as medium-textured Dystrudept and Fragiudept Inceptisols and tend to be moderately to highly acidic and nutrient poor. The bedrock is composed of shale, siltstone, sandstone, and conglomerate with sedimentary and metamorphic rock fragments. Sandstone and conglomerate are interbedded with siltstone and shale. The soil pH range of 3.9-4.7 with a low base saturation is in part due to decades of acidic atmospheric deposition. Thin soil organic horizons of approximately 5-10 centimeters limit carbon storage, as compared to other common northeastern soil types (McHale et al., 2008, Murdoch et al., 2021). In high elevations, soils are thin, rocky, and frequently damaged by winds, ice, snow, and drought (NAS, 2020). Common soil series include Oquaga, Lackawanna, Lewbeach, and Halcott with a temperature/moisture regime of frigid to mesic on lower slopes (Bryce et al., 2010).

Bluestone, a type of sandstone, forms the core of the Catskill Mountains. This substrate was formed when much of the state was covered by a shallow tropical sea that was fed by large rivers running down the Acadian Mountains. Mountain runoff was carried into this sea and over time was galvanized into bluestone. Evidence of this era can still be seen in ripple marks on bluestone slabs and fossilized clam burrows. Bluestone eventually became a prime building material for its ability to split easily, spurring a boom and bust industry in the 1800s (Sharpe, 2017, p. 17).

There are four major escarpments, appearing as long cliff-like ridges that are popular locations for hiking trails and influence major drainage patterns. Best known is the Hudson River Escarpment, which rises 500 meters and delineates the eastern edge of the region 8-10 km from the Hudson River. The highest peaks jut up to 1,000 to 1,275 meters in the Esopus and Schoharie Creek Watersheds (NAS, 2020). There are 33 peaks over 3,500 ft in elevation in the region. Waterfalls are common in the area, lakes are less common, and streams contain cold to cool water with bedrock, boulder, cobble, and gravel substrates (Bryce, et al., 2010). The Delaware River Valley, Susquehanna River Valley, and Finger Lakes Region lie to the west (NAS, 2020).

Legacy of Disturbance

Natural disturbance regimes in the Catskills include wind, ice storm, and fire. The Wisconsin ice sheet also retreated 10-14,000 years ago, greatly altering landscape features, soils, and hydrology (McIntosh and Hurley, 1964). Anthropogenic disturbances, such as fire, agriculture, logging, and human settlements, changed the composition of the biotic community in the Catskills. The legacy of these intensive disturbances still impact the distribution and abundance of species today (McIntosh, 1972). Although many of the resource extraction practices of the 18th and 19th centuries have ceased, their impact can still be observed. For example, oak-dominated areas harken back to land management practices by Native Americans, whereas a lack of oaks suggests a history of selective logging, a pattern which can be seen in the central Catskills (Driese et al., 2004). Despite this history of intensive land disturbances, discussed in greater detail below, there are many indications of recovering habitats and populations. Most notably, white-tailed deer, black bear, brook trout, fisher, and bald eagles are examples of species that have returned from the brink of extinction to once again populate this landscape (Van Valkenburgh and Olney, 2004), all of whom help tell the region’s story as one of nature’s triumphs (Stradling, 2010).

Human History

The Catskills is the traditional territory of the Mohicans to the east, Haudenosaunee (Kanien'kehá:kah/Mohawk) to the West, and the Wabanakis and Hurons to the North (Academics of Science, 2020, Stradling, 2007, p. 21).

The Algonquin-speaking Lenni Lenape lived on lands that are now encompassed by New Jersey, Delaware, eastern Pennsylvania, and southern New York. The Esopus tribe was a Lenape clan that lived in present day Ulster and Sullivan counties.

In the Western Catskills, the Lenape clan was called Munsee, “the people of the stony country.” They lived along the east and west branches of the Delaware River. They were given the name Delaware Indians by the first Europeans settlers in the 1600s who named the river in honor of Thomas West, third Baron De La Warr, who became the Virginia Colony’s first governor. The river sustained the Lenni Lenape by providing shad, elk, black bear, and deer (Sharpe, 2017, p. 61).

These indigenous people actively managed the landscape through controlled and frequent burning to facilitate the growth of grasses, berries, and game species habitat. Kudish (2000) notes that these management practices resulted in southern hardwood forests in the valleys and lower slopes, containing species adapted to fire, and northern hardwood forests on the upper slopes and interior forests.

Settlements were located near present-day Hudson, Mohawk, and portions of the Delaware Valley with the mountainous areas being used seasonally for fishing and hunting (Stradling, 2010, p. 22). Wildlife populations supported by vast forest tracts served as important protein sources to supplement agricultural practices, which likely date back over 1,000 years (NAS, 2020; Stradling, 2010, p. 21).

As indigenous populations declined due to colonization, forest composition changed with the absence of these management practices, resulting in dense stands with an estimated understory (NAS, 2020). The fur trade between indigenous people and Europeans started in the early 1600s and quickly accelerated thereafter, causing fur-bearing species to rapidly decline and forest food webs to be widely disrupted (NAS, 2020).

As a note of interest, the words Esopus, Neversink, Pepacton (marriage of the waters in Lenni-Lenape), and Pakatakan are words from Native American languages (Sharpe, 2017, p. 64; Stradling, 2010, p. 22).

In comparison to the rest of the northeast, Euro-American settlements in the 1700s were slow to establish in the Catskills, in part due to soil quality, rough terrain, and conflicting land claims (NAS, 2020); factors that limited the population density and farming intensity for decades (Stradling, 2010, p. 24). By the late 1700s, agrarian settlements in the Esopus and Schoharie valleys increased as more European people emigrated from Connecticut and the Hudson River Valley, ushering in an era of forest clearing. These clearings were used for crops, such as rye, oats, and wheat, and as pasture for livestock, initially sheep followed by cows and horses (NAS, 2020).

Many of the earliest farms are still in existence today, as they were first sited on productive soils. Later farmsteads were often sited on marginal hillside soils and abandoned for the promises of the Ohio Valley’s prime soils, a trend that was heavily influenced by the opening of the Erie Canal in 1821. Many even-aged stands can be connected back to this period of farmland abandonment (NAS, 2020). Dairy farming boomed by the late 1800s with the railroads connecting Catskill farmers to urban markers, most notably New York City. Agricultural settlement peaked by around 1875 with the majority of the Catskills being impacted by humans (Stradling, 2010, p. 44).

In concert with other areas in the northeast United States, the land-based industries of the 18th and 19th centuries took an ecological toll on the Catskills, impacting approximately 94% of the region. Hardwoods were largely harvested, hemlocks were stripped of their bark, and spruce, pine, basswood, and white birch were used in paper mills. Pastures were cleared, bluestone was mined, and factories dotted the landscape. As these activities peaked, many species saw record low populations. For example, in the early 1820s, trout were gone from Saratoga Lake, and wolves, moose, elk, and panthers were extirpated (van Valkenburgh and Olney, 2004).

The lack of productive soils and adequate growing season led to the advancement of other industries in their place. Of these practices, the tanning industry may have the most lasting legacy in the Catskills. Peaking in the mid-1800s and concentrated in the northern portion of the region, tanneries were largely responsible for the decline in late successional forests, most notably the eastern hemlock as a foundational species (Stradling, 2010, p.35).

Hides were transported to the tanneries from Hudson River ports, treated with the tannins from hemlock bark, and shipped back out of the Catskills to urban markets. Over 60 tanneries changed stream biochemistry and lowered the pH from waste products, which in turn degraded the aquatic ecosystem and caused a crash in brook trout populations.

Greene County was home to the most productive tanneries, producing more leather than the rest of the state by 1825 (Stradling, 2010, p. 25) The largest tannery, owned by Zaddock Pratt, employed about 30,000 men and stripped ten square miles of hemlock forest, containing almost half a million hemlock trees in a 20 year period. The leather produced in these facilities boosted the Catskill economy to be one of the largest producers of shoe soles between about 1820-1870 with many products landing in New York City (Stradling, 2010, p. 29). Economically, tanneries provided seasonal employment and supplemental income to the area’s farming communities.

In addition to direct impacts, the tannery industry facilitated subsequent extractive practices and additional ecological impacts. Deciduous, hardwood trees such as maples, beech, and ash, filled the gaps left behind by hemlocks, which were used to make barrel hoop wood in cooperage mills and furniture. This new forest composition would have had a ripple effect on nutrient cycling rates, soil chemistry, microbial populations, stream pH, and loading of natural organic matter to streams (NAS 2020).

Tannery access roads were used for logging and charcoal production. Hemlock slashings were often burned, cleared, and used for pastureland. Hemlock logs, along with white pine and red spruce, were sometimes floated to downstream sawmills for lumber. Additionally, small hydro-powered sawmills could be found on nearly every Catskill waterway.

Horses were used in many of these activities and needed extensive pastureland and hayfields. Mature hemlocks were stripped of bark and left to rot with dry, flammable crowns, which increased forest fire events in the late 1800s (NAS, 2020). These fires resulted in large forest gaps and increased the abundance of pioneer species, such as birch and black cherry (Kudish, 2000).

After more than a century of intensive resource extraction, these practices declined at the turn of the 20th century, as the resource base gave out. The boom and bust story of extractive industries in the Catskills resulted in a lasting ecological legacy. This legacy is still evidenced by a lack of stable coarse woody debris, channel characteristics, and streambed material, for example.

Railroads, steamboats, and automobiles made the region less isolated and soon supported the Catskills as a coveted tourism destination (NAS, 2020). The once plentiful natural resources of the region first “connected local hands to city money;” a linkage that was reinforced by the interwoven histories of settler and frontier, wilderness and economy, success and failure, and overuse and recovery (Stradling, 2010, p. 21). Interestingly, the history of ecological collapse sets the stage for the region’s pioneering conservation story; one that initiated in a denuded landscape, rather than a pristine wilderness (Stradling, 2010, p. 121).

Conservation History

Catskill Park and Forest Preserve

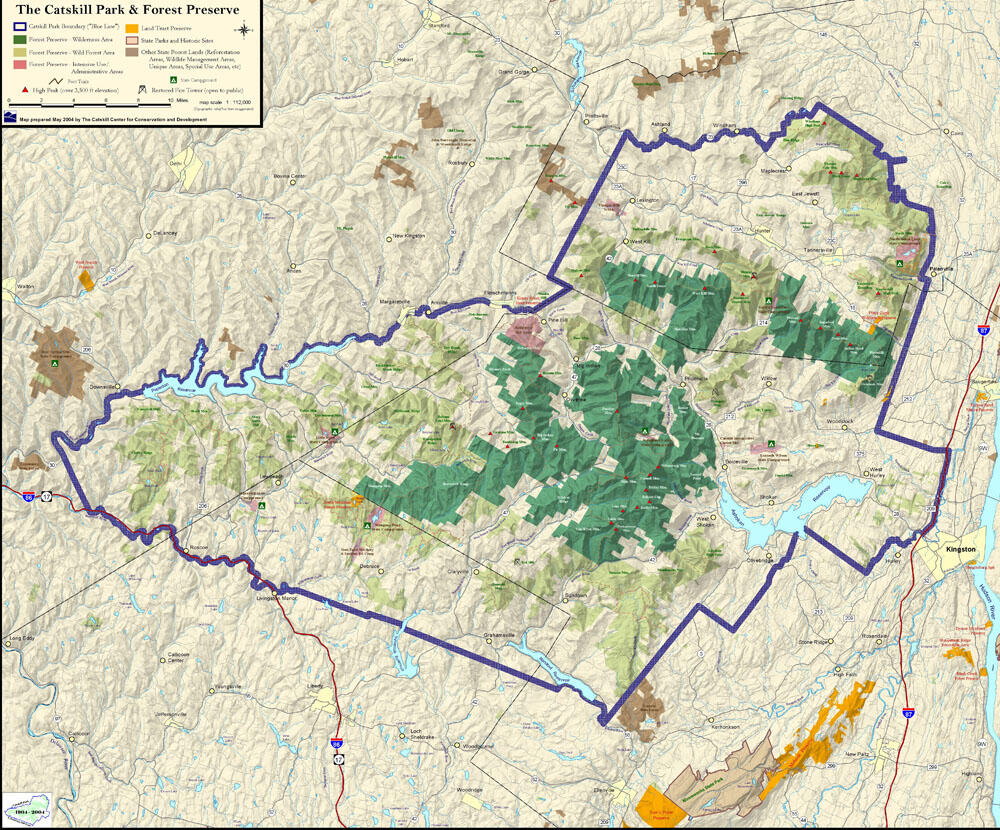

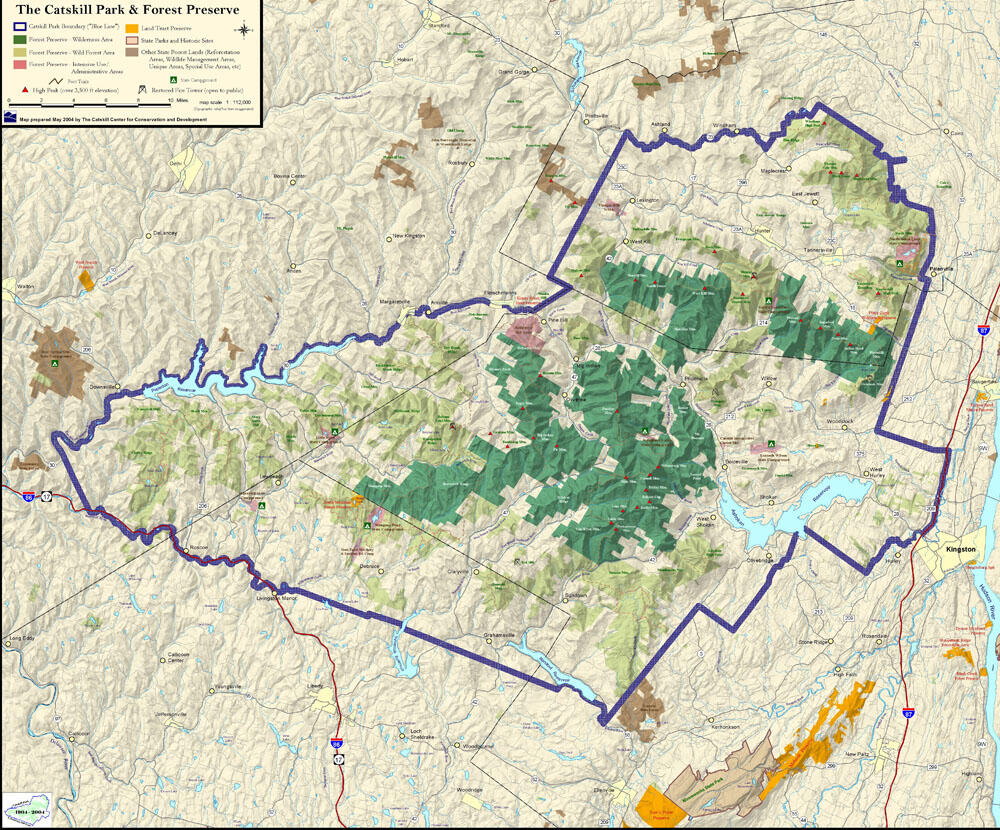

In 1904, New York State established the Catskill Park, which now encompasses 705,500 acres of land (NYS DEC, 2022). Approximately 300,000 acres of land within the Catskill Park belong to the New York State (NYS) Forest Preserve with the remaining acres held in private ownership. Logging, road building, and other disruptive practices are prohibited in the publicly held areas (Driese et al., 2004), as mandated by Article XIV of the New York State Constitution, which states that these lands are held in the public domain in perpetuity; “forever kept as wild forest lands.” Approximately 35% of the private land in the Catskill Park is owned and managed by the New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). Additional private lands contain more small, individually owned woodlots than parcels owned and operated by industry scale timber companies (Van Valkenburgh et al., 2004).

The Catskill Forest Preserve’s initial 34,000 acres were established through an amendment to the larger Adirondack Forest Preserve legislation. At this time, conservation efforts were focused on the Adirondacks, in part motivated by lessons learned from overextraction in the Catskills, and the Catskills themselves were thought to be beyond recovery (NAS, 2020). Some of these lands went under state ownership after natural resources were extracted, allowing ecological recovery to occur going forward. Rather than the more typical preservation approach of protecting intact landscapes and maintaining their integrity over time, the Catskills conservation story focuses on the potential for ecological restoration and recovery. This approach requires active management and even manipulation, busting many of conservation’s wilderness myths (Stradling, 2010, p. 121). The Catskill Forest Preserve tripled in acreage by 1916 and again doubled in size by 1944 to reach 215,000 acres. Bond acts of the 1960s and 1970s brought the Preserve to its current area (NAS, 2020).

The creation of the Catskill Forest Preserve was a landmark event, representing one of the first significant preservation efforts in the United States and introducing the idea of wilderness into legislation (Robinson, 2007 p.7; Stradling, 2010, p.1). Further, this approach ushered in an era of state forestry, establishing governmental authority of environmental management (Stradling, 2010, p. 137).

These efforts were part of Great Depression-era conservation practices aimed in part at solving unemployment and economic recovery. As part of the Hewitt Amendment, landowners of the Catskills were provided opportunities to sell unprofitable parcels to the government in order to advance reforestation efforts. These policies allowed the government to not only preserve existing forests but increase forested acres as well (Stradling, 2010, p. 162-3). As the state continued to acquire lands, a different conservation story unfolded.

Rather than preserve the most pristine and contiguous areas, land acquisition in the Catskills more often involved the parcel by parcel preservation of heavily used areas that were then allowed to recover (Van Valkenburgh and Olney, 2004). As much of the watershed has now recovered from intensive resource extraction, the Catskill story demonstrates ecosystem resiliency and the potential of multi-use systems. This model is especially relevant to the socio-ecological systems that will continue to characterize the vast majority of the planet in the 21st-century and beyond.

Today, approximately 143,000 acres of Preserve lands are designated as wilderness and can only be accessed by foot. The five wilderness areas include Big Indian, Slide Mountain, Hunter-West Kill, Indian Head, and Windham-Blackhead Range. Wilderness areas must be at least 10,000 acres in size, hold ecological, geological, scenic, or social value, and be lacking in apparent human influence (Van Valkenburgh, 2014).

Wild forests are designated on 130,000 acres of land and offer a range of recreational activities, including hiking, camping, cross-country skiing, and mountain biking. Snowmobiling and horseback riding are also permitted in certain areas. These areas can withstand a higher level of use and generally lack a sense of remoteness in comparison to wilderness areas.

The management objective of these areas is to “accommodate present and future public recreation needs in a manner consistent with article XIV of the state constitution” without impairing wildlife or compromising the character of the area. To achieve this objective, resources may require active management (Van Valkenburgh, 2014). State recreation areas comprise about 6,000 acres and include the Belleayre Mountain Ski Area, campgrounds, picnicking/day use areas, boat launches, and fishing and swimming areas.

The Forest Preserve includes remote backcountry with over 300 miles of trails in total. Trails range from easy one-mile segments to the ambitious 94-mile section of Long Path. These resources stem from an effort that started in the 1920s to develop the Forest Preserve for recreation (Stradling, 2010, p. 151).

The DEC uses the Catskill Park State Land Master Plan, a land classification system, and individual unit management plans to balance recreational use with resource protection (NYS Department of Environmental Conservation, 2022).

Today, this region is known for its nature-based economy, private lands that allow people to maintain their place-based connections and rural livelihoods, and commitment to wilderness protection.

Drinking Water

Approximately 45% of the NYC Watershed is found in the Catskill Park and roughly 65% of the Catskill Park is within the NYC Watershed (Van Valkenburgh, 2014). The Ashokan, Rondout, Cannonsville, Schoharie, Pepacton and Neversink reservoirs provide approximately 90% of New York City’s water supply (Driese et al., 2004). Negotiations around watershed management date back to the early 1900s, but came to a head in the mid-1990s. These often contentious discussions were facilitated by Governor Pataki’s office between NYC, NYS, watershed towns, and various environmental groups. Finally in 1997 a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) was signed to protect water quality and foster a sense of community vitality. A land acquisition program was initiated as an outcome of the MOA to be implemented by the DEP. The goal was to maintain high water quality in the watershed by limiting development and protecting important habitats, including wetlands, floodplains, stream corridors, forests, and agricultural lands. These measures added value beyond water quality, as wildlife, scenic view sheds, and outdoor recreational assets were also protected (Van Valkenburgh, 2014).

The Catskill and Delaware Watersheds gained international attention as a conservation success story and living argument for investing in ecosystem services (Stradling, 2010, p. 143). New York City paid over $1 billion in Catskill land preservation. Starting with the 1988 publication in Nature, this narrative continues today as a flagship example of the power of investing in ecosystem services to achieve a win-win solution for economic development and ecological preservation, casting new light on the traditional debate (Blanchard et al., 2015).

Today, New York City owns more than 125,000 acres of land in the region, including 40,000 acres within the Catskill Park. The region’s 19 reservoirs and aqueducts provide over a billion gallons of drinking water to New York City each day, making the Catskill/Delaware water supply the largest unfiltered system in the United States (NAS, 2020). The water is only disinfected with chlorine and ultraviolet due to the largely undeveloped and intact forested land cover throughout the Catskills Region (NAS, 2020). The Catskills are often cited as the origin story for watershed management with a hybrid approach that relied upon market-based incentives and regulatory mechanisms. All told, the conservation history of this area presents a compelling question—how might we benefit when nature is conserved, rather than intensively developed and cultivated (Blanchard et al., 2015)?

Research Needs

Knowledge generated by ecological research and monitoring programs has not always effectively flowed to conservation managers to inform on the ground practices. The published literature is infrequently viewed or incorporated into management activities by practitioners (Knight et al., 2008). As a result, decision making by practitioners can be incomplete, based on anecdotal evidence, or stem from internal techniques (Salafasky et al., 2019; Knight et al., 2008). Similarly, areas of focus by researchers can be minimally relevant and not reflect local needs (Dubois et al., 2019). This problem is overall encapsulated by the “trickle-down, transfer, and translate model” of knowledge sharing, which expresses the many barriers involved in peer-reviewed literature trickling to managers, translating results into action, and transferring skills (Knight et al., 2008). Evidence-based conservation approaches emerged at the turn of the 21st-century as an antidote to the overuse of intuition and personal experience in conservation decision making (Dubois et al., 2019). Despite this timeline, evidence-based conservation remains less developed and less frequently practiced in comparison to other fields such as medicine and education (Salafasky et al., 2019). The coproduction of knowledge between practitioners and researchers is needed to overcome the research-implementation problem. Greater overlap of these traditionally separate fields can be achieved through collaborative efforts, such as the CSC, that increase interactions between stakeholders, representing both the experts and the users (Dubois et al., 2019). The CSC helps bridge the research-implementation gap by facilitating the fluidity of knowledge exchange between researchers and practitioners and supporting scientists’ collaborative skill sets and boundary crossing capabilities (Read et al., 2019).

In an effort to bridge the research-implementation gap and address holes in the evidence base prior to decision making, the following research needs were articulated by practitioners based on pressing research questions (Dubois et al., 2019). These needs are shared in this research guide to further facilitate fluid and cohesive knowledge exchange between researchers and managers.

Water Quality

- Monitoring dissolved organic carbon and associated disinfection byproduct precursors

- Impact of cover crops on dissolved phosphorus

- Reconnection of artesian seeps to streams

- Non-point water contaminants (NAS, 2020)

- Turbidity, namely in restored stream corridors during extreme events (NAS, 2020)

Stream Ecology and Restoration

- Landowner outreach for property protection in high stream flow areas

- Baseline assessment of large wood accumulation dynamics

- Modeling stream channel coupled hillslope mass wasting

- Streamflow morphodynamics, sediment flux, and catchment scale turbidity

- Regression relationships for stream channel dimensions

- Cornell culvert model validation

- Aquatic habitat evaluation for stream restoration

- Evaluation of stream management intervention levels

Recreation and Community

- Trailhead sign-in rates

- Recreational impacts on trailless peaks

- Primitive tent site monitoring

- Catskill Forest Preserve carrying capacity

- Trail overuse responses

- Trail modification feasibility study

- Visitor attitudes on intensive trail use

- Community vitality analysis

Biodiversity

- Impact of human visitation on breeding birds

- Black bear-human interactions

- Wood turtle distribution and abundance

Invasive species

- Modeling susceptibility and vulnerability of waterbodies to invasive species

- Co-occurring stressors from invasive species

- Risk assessment of invasive species introductions at trailheads

- High resolution remote monitoring of hemlock health and hemlock wooly adelgid monitoring

Select Organizations

The Catskills are fortunate to have many institutions, both public and private, that have a strong interest in the conservation and management of the Park and surrounding areas. A complete listing of all institutions would be much more extensive, but here we list many of the groups with which the CSC has worked in the first five years of our existence.

Government Organizations and Agencies

Catskill Watershed Corporation

The Catskill Watershed Corporation provides consultation and sponsorship of programs stemming from the 1997 Memorandum of Agreement that gave New York City exemption from drinking water filtration. These programs include the New Sewage Infrastructure Program, Reservoir Recreational Boating Program, Wastewater Treatment Plant Upgrade Program, Land Acquisition, Flood Hazard Mitigation Implementation Program, and more. Their mission is to protect water quality and preserve “communities in the Catskill-Delaware New York City Watershed.”

Helpful Resources:

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYS DEC) was founded in 1970 with the purpose of combining state conservation programs under one umbrella. Their mission is to “conserve, improve and protect New York's natural resources and environment and to prevent, abate and control water, land and air pollution, in order to enhance the health, safety and welfare of the people of the state and their overall economic and social well-being." They fulfill this mission through environmental quality, public health, economic prosperity, social well-being, environmental justice, and individual empowerment. Regions 3 and 4 are both found within the Catskills Region.

Key Contacts:

Helpful resources:

- Permit, licenses, and registration information

- Forest preserve unit descriptions, including the 5 wilderness areas and 15 wild forest areas.

- Catskill Strategic Planning Advisory Group (CAG)

- Northern Catskills Wilderness Management Areas (Region 4)

- State forests: Southern Catskills and Northern Catskills

New York City Department of Environmental Protection

Description: New York City Department of Environmental Protection (NYC DEP) manages New York City’s water supply with the mission to “enrich the environment and protect public health for all New Yorkers by providing high quality drinking water, managing wastewater and stormwater, and reducing air, noise, and hazardous materials pollution.” Their organizational core values include safety, integrity, service, diversity, support, transparency, sustainability, and innovation. NYC DEP implements the extensive Watershed Protection Program to monitor and maintain high quality drinking water. These programs target microbial pathogens, turbidity, nitrogen and phosphorus loading, dissolved organic matter, and other contaminants (NAS, 2020). Their 2018 strategic plan includes 43 initiatives, one of which includes engaging in cutting-edge research.

Helpful resources:

- Pierson, D. 2017. NYCDEP Catskill Reservoirs (NY): water quality, 1984-2011 ver 1. Environmental Data Initiative. https://doi.org/10.6073/pasta/dcf40d86725ae21f7f36aeacd9bb9253 (Accessed 2022-08-10).

Soil and Water Conservation Districts (SWCD)

Soil and water conservation districts are subdivisions of local governments that are tasked with supporting and implementing local level conservation initiatives. These resource management agencies act in cooperation with federal and state agencies and in collaboration with local stakeholders, such as landowners, land managers, and local interest groups. They are important research partners as they often coordinate funding, permitting, and site-level project management. All of the SWCD’s below participate in NYS’s Agricultural Environmental Management program (AEM), which offers technical and financial assistance to farmers to address water quality issues. These agencies were born out of Great Depression-era conservation measures and enabled by legislation in 1937.

Helpful resources:

- Catskill Streams Buffer Initiative, including key contacts

- Stream Management Program, including key contacts and funding information

Delaware County SWCD

Description: The Delaware County Soil and Water Conservation District was created in 1946 with the mission to “provide technical assistance to landowners and local governments for the wise use and conservation of Delaware County’s soil and water resources.” They have over 20 full time employees, many of whom are involved with the NYC Watershed Agricultural Program and Stream Corridor Management Program.

Helpful resources:

- Delaware Watershed Advisory Committee

- Delaware County’s Action Plan for Watershed Management

- Getting to Know Your Streams and Stream Program booklet

Greene County SWCD

Description: The Greene County Soil and Water Conservation District was established in 1961 to facilitate projects pertaining to federal flood control in Windham, NY. Since that time they have developed a “diverse conservation program in response to local needs, which provides assistance to landowners, local municipalities, and state and federal agencies.” Their focal efforts include Catskill Streams Buffer Initiative for landowners with streamside parcels within the Schoharie Reservoir Watershed and Schoharie Watershed Stream Management Program in support of watershed management strategies, as well as several others.

Helpful resources:

- Schoharie Watershed Advisory Committee

- Stream ecosystem data repository

- Grant resources Grant resources

- Stream Management Implementation Program Stream Management Implementation Program

Otsego County SWCD

Description: The Otsego County Soil and Water Conservation District offers a wide variety of services, including the recycling agricultural plastics program, riparian forest buffers project, soils percolation testing, GIS mapping, and agricultural assessments. They have technical expertise in the North Atlantic Aquatic Connectivity Collaborative (NAACC) database.

Helpful resources:

Schoharie County SWCD

Description: The Schoharie County Soil and Water Conservation District was the first county soil and water district established in New York State in 1940, when the need to preserve the area’s natural resources was first recognized. Their mission is to “assist individual landowners, groups, and units of government with any natural resource concerns.” They provide technical assistance in agriculture, municipal conservation, stream management, agricultural assessments, fish sales, tire sidewall removal, pond evaluations, stream permitting assistance, stream design assistance, and pond site evaluations.

Sullivan County SWCD

Description: The Sullivan County Soil and Water Conservation District’s projects include flood mitigation, the Rondout Neversink Stream Program, and fish sale programs. Their services include pond site investigations, landowner site visits, and agricultural assessments. The mission of the Rondout Neversink Stream Program is to “protect and restore stream system stability and ecological integrity by providing for the long-term stewardship of streams and floodplains.” This program is a partnership project funded by NYC DEP. Their programs and grants center on municipalities and private lands at the NYC Watershed headwaters in Denning (Ulster County) and Neversink (Sullivan County), including the Upper Rondout Creek, Upper Neversink River, Chestnut Creek, and tributaries that run into the Rondout and Neversink Reservoirs.

Helpful resources:

- Annual anglers symposium

- Landowner guides on edible buffers, native plants, biodiverse buffers, and soil health

- Support and funding information here and here

- Stream management plans and action plans

Ulster County SWCD

Description: The Ulster County Soil and Water Conservation District has over 40 years of experience as an action oriented group “responsible for the design and implementation of engineering and agronomic practices intended for the improvement of water quality and the preservation of the County’s natural resources, in both rural and urban capacity.” Programs include NYS non-point source pollution, site inventory and evaluation, stormwater and erosion control, riparian buffers, and more. They partner with Cornell Cooperative Extension of Ulster County and NYC DEP to run the Ashokan Watershed Stream Management Program.

Non-Profit Organizations

Cary Institute

Founded in 1983, Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies has a mission to “generate rigorous scientific knowledge about ecological systems and their importance to human well-being.” Its scientists are global experts in the ecology of freshwater, forests, disease, and cities. Through collaborative efforts, they apply science to policy and management that protects the environment and improves human well-being.

Catskill Center for Conservation and Development & Catskill Visitor Center

Description: Located in Arkville, the Catskill Center has a mission to “protect and foster the environmental, cultural, and economic well-being of the Catskills Region.” Dating back to the late 1960s, the organization has been involved in efforts to protect land within the Catskill Park and Catskill Forest Preserve. Focal programs include regional collaboration, stewardship of public and private lands, and inspiration for responsible economic growth. Its Streamside Acquisition Program, in partnership with NYC DEP, seeks to purchase streamside land in order to protect water quality. It is part of the Catskill Park Coalition and Catskill Park Advisory Committee. The Catskill Center operates the Maurice D. Hinchey Catskills Visitor Center, hosts a stewards program, and functions as a land trust. It is a 501(c)(3) guided by a volunteer board of directors and funded by private donations, foundations, and a variety of New York State and federal agencies.

Helpful resources: Digital elevation models for general mapping and watershed analysis

Catskill Forest Association

The Catskill Forest Association’s purpose is to provide “forestry education and services to private Catskill landowners.” The organization takes care of over 86,000 acres of private property. Services include wildlife habitat management, invasive species management, tree care, and property mapping.

Catskills Regional Invasive Species Partnership (CRISP)

CRISP was formed in 2005, and is one of eight NYS Partnerships for Regional Invasive Species Management (PRISM). It is hosted by the Catskill Center for Conservation and Development with the mission to “promote education, prevention, early detection, and control of invasive species to limit their impact on the ecosystems and economies of the Catskills.” They use the citizen science platform iMapInvasives to report invasive species observations and share distribution information with scientists and natural resource managers.

Helpful resources:

Catskill Mountainkeeper

Description: The mission of the Catskill Mountainkeeper is to “protect our region's forests and wild lands; safeguard air and water; nurture healthy, equitable, and sustainable communities; empower environmental justice communities; and accelerate the transition to a 100% clean and just energy future in New York State and beyond.”

Catskill Water Discovery Center

The mission of the Catskill Water Discovery Center is to “educate people of all ages about the precious nature of, and threats to our planet’s most vital resource–pure water.” The organization engages the public about the NYC water supply system through programs, exhibits, and events about water resources, using the Catskill and Delaware Watershed as a living classroom to connect the history and lived experiences of communities connected to these watersheds. Its partnerships include the Arkville Recreation Hub, the Catskill Watershed Corporation, Watershed Agricultural Council, NYC DEP, Central Catskills Chamber of Commerce, the Catskill Center, Catskill Forest Association, Frost Valley YMCA, and the Ashokan Center.

Helpful resources:

- Of Rivers and Reservoirs: The New York City Water Story interpretive exhibit

Cornell Cooperative Extension (4 offices)

Description: With offices in every New York county and all boroughs of New York City, the Cornell Cooperative Extension has a mission to “enable people to improve their lives and communities through partnerships that put experience and research knowledge to work.” As a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, it focuses on clean water, local farms, invasive species, and more. It is part of the land grant system, which is a partnership between county, state, and federal government and administered in New York State through Cornell University. The county offices below are located in the Catskills region and operate independently, serving the needs of each county.

Beaverkill Land Trust

Description: Beaverkill Land Trust is an accredited land trust that owns and holds conservation easements on “ecologically important natural lands in the Beaverkill Valley region.” These protected areas are managed for open space, recreation, education, and the benefit of the general public.

Delaware Highlands Land Conservancy

Description: The Delaware Highlands Land Conservancy is an accredited land trust with 18,000 acres of protected land. its mission is to “conserve the forests, farmland, clean waters, and wildlife habitat of the Upper Delaware River region.” The Conservancy has offices in Beach Lake, PA and Barryville, NY.

Helpful resources:

Delaware River Watershed Initiative

The Delaware River Watershed Initiative works to reduce pollution, protect headwaters, and promote water-smart practices with the mission to “protect the rivers and streams that provide drinking water for more than 15 million people across four states.” They deploy a scientific approach to water quality management through modeling, monitoring, and community science and partner with the Academy of Natural Science of Drexel University, the Open Space Institute, Institute for Conservation Leadership, Stroud Water Research Center, and dozens of others.

Helpful resources:

- View The Nature Conservancy’s short film on the Delaware River Basin Watershed

Friends of the Upper Delaware

Description: The mission of Friends of the Upper Delaware is to “protect and restore the Upper Delaware River Watershed for the benefit of local economies, communities, people, and the environment.” The Friends partner with other groups, such as the Alliance for the Upper Delaware River Watershed, the Upper Delaware River Tailwaters Coalition, and the Coalition for the Delaware River Watershed. The organization is involved in research on the management of invasive knotweed.

Helpful resources:

The Michael Kudish Natural History Preserve

The Michael Kudish Natural History Preserve holds 101 acres of permanently protected land for research related to Catskill natural history studies. Its mission is to “increase awareness and support of environmental conservation, scientific research, and long-term sustainability through education, recreation, and artistry.” The preserve is privately and grant funded.

Helpful Resources:

Mountain Top Arboretum

The mission of the Mountain Top Arboretum is to “provide for the Catskills Region a unique and beautiful mountain top environment for a living sanctuary of native and exotic trees and shrubs.” The Arboretum focuses on applied horticulture, environmental stewardship, and public education. Its 178 acres sit at 2,400 feet in elevation and feature trails, boardwalks, and an education center.

New York Natural Heritage Program

The New York Natural Heritage Program is a program of SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry and primarily funded by NYS DEC. Its mission is to “facilitate the conservation of New York’s biodiversity by providing comprehensive information and scientific expertise on rare species and natural ecosystems to resource managers and other conservation partners.” The resources below, as well as many others on the organization’s website, are designed to assist land managers, decision makers, planners, scientists, and community members to better understand New York’s natural communities.

Helpful Resources:

- Online conservation guides

- Databases for rare plants and rare animals

- Ecological communities of NYS reports

- Riparian Opportunity Assessment, including a data explorer tool

- Modeling and analytics tools

Rondout-Esopus Land Conservancy

The mission of the Rondout-Esopus Land Conservancy is to “protect and preserve natural resources and open space while sustaining the scenic beauty and rural character in the Rondout and Esopus Watersheds and adjacent areas.” It is a member of the Land Trust Alliance and has conserved 4,000 acres through 55 conservation easements. The Conservancy has identified 11 priority conservation areas.

Helpful Resources:

- Maps of priority conservation areas (overview and individual maps)

The Nature Conservancy

The Nature Conservancy’s Catskill Mountain Program is one of its eight landscape scale programs of the Eastern New York Chapter. This program started in 2003 with the goal of “protecting, through acquisition, easements and land use planning, the 415,000 acres of remaining interior forest blocks to prevent habitat fragmentation; reducing the impacts of invasive species and promoting and enhancing research and policy development on atmospheric deposition of pollutants.” These forest blocks include Beaverkill, Bear Pen Valley, West Kill Wilderness, Catskill Escarpment, Sugarloaf, and Panther Mountain. The Nature Conservancy runs a revolving fund called the Catskill Land Protection Fund, which assists in land acquisition efforts.

Otsego County Conservation Association

The mission of Otsego County Conservation Association is to promote “the appreciation and sustainable use of Otsego County’s natural resources through research, education, advocacy, planning and resource management and practice.” Its research and management projects focus on invasive species.

Helpful Resources:

Watershed Agricultural Council

The mission of the Watershed Agriculture Council is to “promote the economic viability of agriculture and forestry, the protection of water quality, and the conservation of working landscapes through strong local leadership and sustainable public-private partnerships.” The Council manages 120,000 acres of forests and 32,000 acres of conservation easements, while supporting the implementation of agricultural and farming best practices.

Helpful Resources:

- WAC’s conservation activities interactive map, including participating landowners

Woodstock Land Conservancy

Since 1987, the Woodstock Land Conservancy has worked for “the protection and preservation of the open lands, forests, water resources, scenic areas and historic sites in Woodstock and the surrounding area.” The Conservancy has protected more than 1,000 acres and is accredited by the Land Trust Alliance.

Funding

Open Space Institute

The Open Space Institute (OSI) “protects scenic, natural and historic landscapes to provide public enjoyment, conserve habitat and working lands, and sustain communities.” Through land acquisition, funding, research, and advocacy, OSI has partnered in projects that resulted in the protection of roughly 2.3 million acres in the eastern US and Canada. In the Catskills the Institute has acquired 18,500 acres of Beaverkill Valley’s forests and preserved 21,000 acres of Catskill forests, including 300 acres on Overlook Mountain. The organization provides grants and low-cost loans for land protection efforts in the eastern United States through its Conservation Capital Program. Forests, wildlife habitat, and water protection are areas of particular focus. Funding information can be found here.

William Penn Foundation

The William Penn Foundation is a family foundation focusing on Philadelphia and the surrounding Delaware River Watershed region. Its mission is to “to help improve education for children from low-income families, ensure a sustainable environment, foster creative communities that enhance civic life and advance philanthropy in the Greater Philadelphia region.” Specific to watershed protection, the Foundation focuses on practices, policies, and public engagement in support of aquatic life, recreation, forest protection, agricultural protection, and stormwater solutions.

Helpful Resources:

Stream Management Implementation Program Grants

These grants focus on stream stewardship projects by watershed, specifically in water quality, education, outreach, and community training. Stewardship practices could include erosion control, floodplain management, stormwater best management plans, stream crossings, and more.

Helpful Resources:

- Grant application materials can be found by watershed: Rondout/Neversink, Ashokan, Schoharie, Delaware

- Support and funding opportunities information sheet

- List of funded grants

Catskills Streams Buffer Initiative

The goal of the Catskills Streams Buffer Initiative is to “inform and assist landowners in better stewardship of their riparian (streamside) area through protection, enhancement, management, or restoration.” DEP, County Soil and Water Conservation Districts, and Cornell Cooperative Extension assist riparian landowners in the Catskills through application-based grants to offer financial, labor, and material support.

Helpful Resources:

Research Permits

DEC permit, licenses, and registration information

More Resources

CSC Data Portal is a data repository with over 25 projects about ecology and environmental monitoring in the Catskills Region.

New York City Open Data hosts an open access data platform.

Catskill Environmental Research and Monitoring (CERM) Conference “brings together researchers and natural resource managers working in the Catskills to share research and ideas and to provide networking opportunities.”

Getting to know the area

- Restaurants and lodging information

- Catskill Mountain Region Guide

- ScenicCatskills.com provides lodging, dining, and services guides

- Visitor’s Guide

- For recreational outings, see the Adirondack Mountain Club’s two chapters in the Catskill area- the Albany Chapter and the Mid-Hudson Chapter

Literature Cited

Adams, M. S., & Parisio, S. J. (2013). Biodiversity elements vulnerable to climate change in the Catskill High Peaks subecoregion (Ulster, Delaware, Sullivan, and Greene Counties, New York State). Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1298(1), 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12267

Audubon. 2018a. Catskills Peaks Area. Retrieved August 9, 2022, from https://www.audubon.org/important-bird-areas/catskills-peaks-area

Audubon. 2018b. Ashokan Reservoir Area. Retrieved August 9, 2022, from https://www.audubon.org/important-bird-areas/ashokan-reservoir-area

Blanchard, L., Vira, B., & Briefer, L. (2015). The lost narrative: Ecosystem service narratives and the missing Wasatch watershed conservation story. Ecosystem Services, 16, 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2015.10.019

Bryce, S.A., G.E. Griffith, J.M. Omernik, et al. 2010. Ecoregions of New York. Reston, VA: U.S. Geological Survey, map scale 1:1,250,000

Driese, K. L., Reiners, W. A., Lovett, G. M., & Simkin, S. M. (2004). A vegetation map for the Catskill Park, NY, derived from multi-temporal landsat imagery and GIS Data. Northeastern Naturalist, 11(4), 421–442. https://doi.org/10.1656/1092-6194(2004)011[0421:avmftc]2.0.co;2

Fahey, T. 2001. Forest Ecology. In Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, Volume 3. Academic Press.

Howard, T. G., & Schlesinger, M. D. (2013). Wildlife habitat connectivity in the changing climate of New York’s Hudson Valley. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1298(1), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12172

Kudish. M. 2000. The Catskills: A Forest History. Purple Mountain Press. Fleischmanns, NY. 217 pp.

Lovett, G. M., Arthur, M. A., Weathers, K. C., & Griffin, J. M. (2013). Effects of introduced insects and diseases on forest ecosystems in the Catskill Mountains of New York. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1298(1), 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12215

McIntosh, R. P., & Hurley, R. T. (1964). The Spruce-Fir Forests of the Catskill Mountains. Ecology, 45(2), 314–326. https://doi.org/10.2307/1933844

McGuire, J. L., Lawler, J. J., McRae, B. H., Nuñez, T. A., & Theobald, D. M. (2016). Achieving climate connectivity in a fragmented landscape. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(26), 7195–7200. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1602817113

McHale, M.R., Murdoch, P.S., Burns, D.A., and Baldigo, B.P., 2008, Effects of forest harvesting on ecosystem health in the headwaters of the New York City water supply, Catskill Mountains, New York: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2008–5057, 22 p., also available online.

Murdoch, P. S., Burns, D. A., McHale, M. R., Siemion, J., Baldigo, B. P., Lawrence, G. B., George, S. D., Antidormi, M. R., & Bonville, D. B. (2021). The Biscuit Brook and Neversink Reservoir watersheds: Long-term investigations of stream chemistry, soil chemistry and aquatic ecology in the Catskill Mountains, New York, USA, 1983–2020. Hydrological Processes, 35(10), e14394. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.14394

National Academies of Sciences (NAS). 2020. Review of the New York City Watershed Protection Program. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NYS Dept. of Environmental Conservation. (n.d.). Welcome to the Catskills. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://www.dec.ny.gov/outdoor/120094.html

NYS Department of Environmental Conservation. (n.d.). Catskill Park Map and Guide. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://www.dec.ny.gov/docs/lands_forests_pdf/catskillmapguide2018.pdf

NYS Department of Environmental Conservation. (n.d.). Birth of the Blue Line in the Adirondack and Catskill Parks. Birth of the Blue Line in the Adirondack and Catskill Parks - NYS Dept. of Environmental Conservation. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://www.dec.ny.gov/lands/110552.html

Nicholas A. Robinson, "Forever Wild": New York's Constitutional Mandates to Enhance the Forest Preserve

Sharpe, L. T. (2017). p. 61. In The Quarry Fox and other critters of the wild catskills. essay, The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

Stradling, D. (2007). Making Mountains: New York City and the Catskills. University of Washington Press.

Stradling, D. (2010). The Nature of New York: An Environmental History of the Empire State. Cornell University Press.

Van Valkenburgh, N., Olney, C. W., & Teich, T. (2004). The Catskill Park: Inside the Blue Line, the Forest Preserve & Mountain Communities of America's first wilderness. Black Dome Press.

More Resources

The Ashokan Catskills, The Hudson Valley & Catskill Mountains: Only the Best Places

The Catskill Park: Inside the Blue Line

The Catskills: A Geological Guide

Catskill Peak Experiences

Natural Resources: 50 Stewards of the Catskills